September 30, 2021, marks the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

The federal holiday was created to honour the lost children and survivors of residential schools, their families and communities.

In the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 87th Call to Action, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame wants to honour this National Day for Truth and Reconciliation by recalling and celebrating Indigenous excellence and achievement in sport in our province and sharing some of the hardships and challenges those athletes and builders faced. At the same time, we also want to honour and remember all those residential school survivors — though particularly our inductees — as part of this first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

We also want to share other resources that chronicle the stories and achievements of some of Saskatchewan’s Indigenous sporting legends.

While the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is a time to learn and reflect on both the history and ongoing impacts of residential schools, the work of reconciliation is continuous.

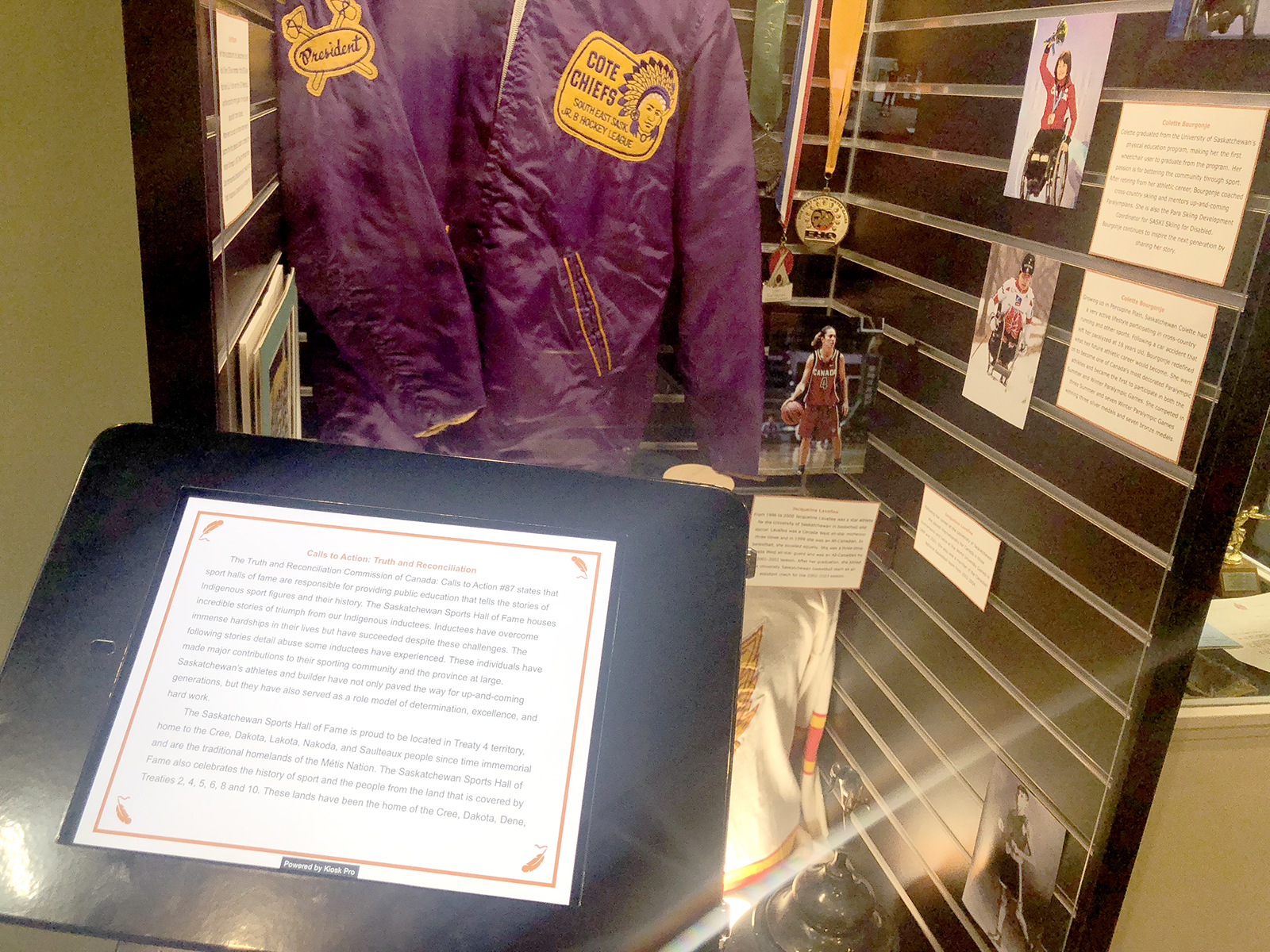

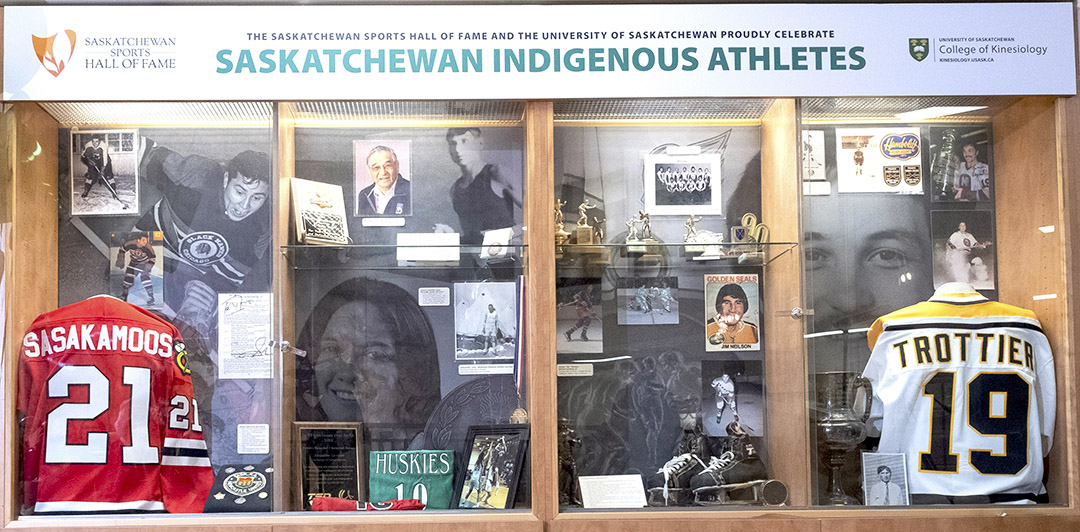

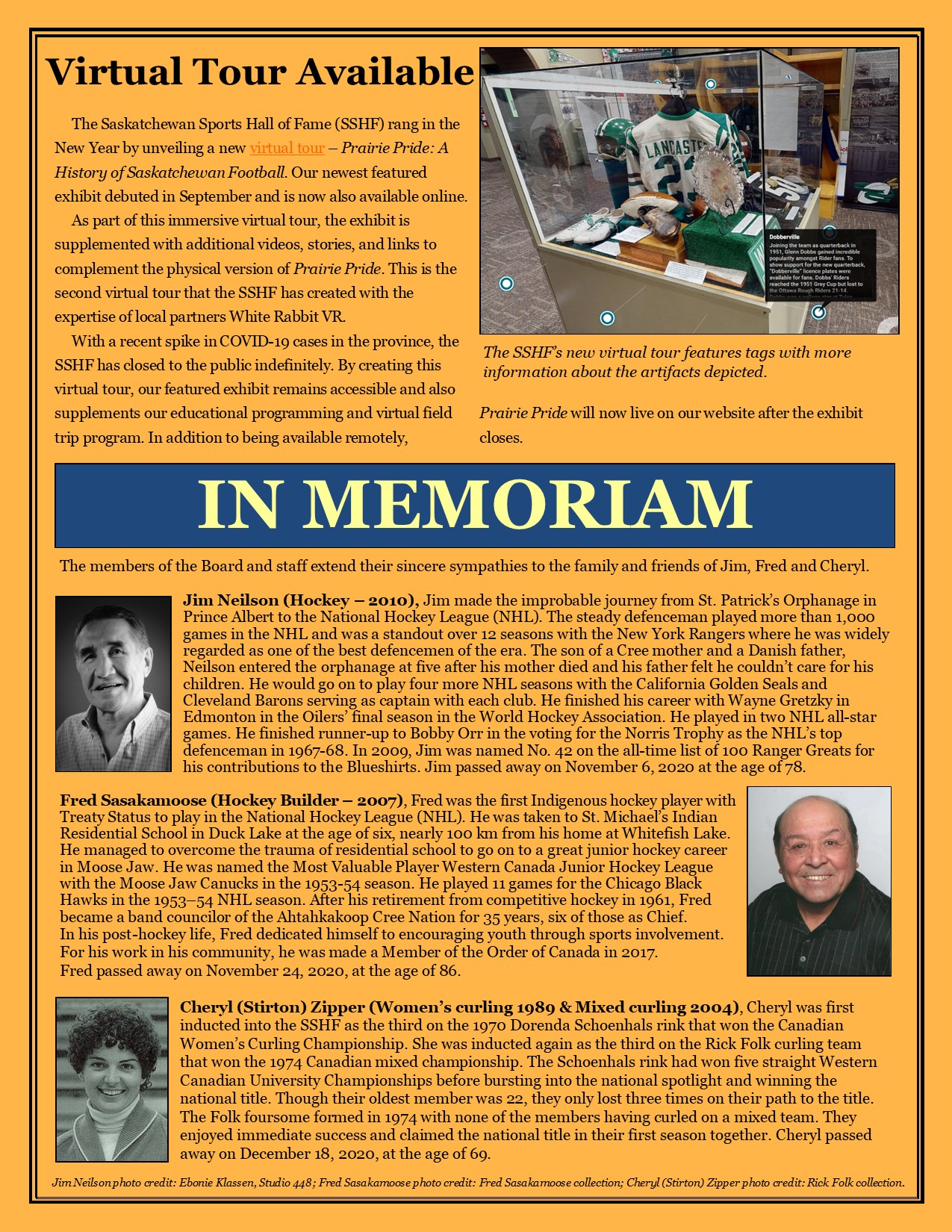

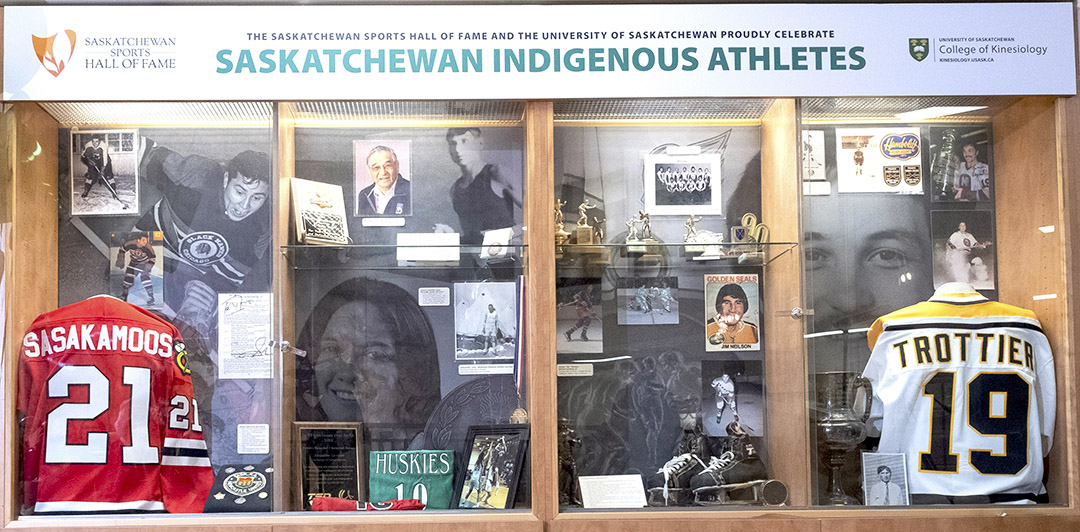

To that end, the SSHF wants to continue to preserve and share the history of Saskatchewan’s Indigenous athletes. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame has a display case and video kiosk celebrating Saskatchewan Indigenous athletes and their achievements on permanent display in the Physical Activity Complex at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Kinesiology in Saskatoon.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame currently has nine individual athletes who identify as Indigenous who have been inducted. Those athletes and builders are: Paul Acoose, Tony Cote, Alex Decoteau, David Greyeyes, Jacqueline Lavallee, Jim Neilson, Claude Petit, Fred Sasakamoose, and Bryan Trottier.

Our nomination process is open to the public and if you believe you know of an athlete, builder or team that deserves inclusion into the Hall of Fame we invite you to nominate them. You can learn more about that process here.

Colette Bourgonje is a member of the SSHF’s 2021 Induction Class and has appeared at 10 Paralympic Games – both Winter and Summer — and has 10 Paralympic medals. While we look forward to being able to announce her induction date, we were pleased to have Colette be part of our Never Give Up program. Colette, who is of Métis ancestry and grew up in Porcupine Plain, shared her inspiring story with school children across the province through a virtual presentation.

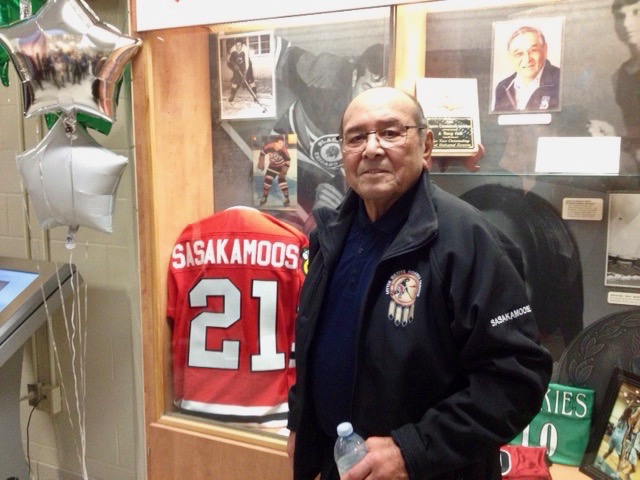

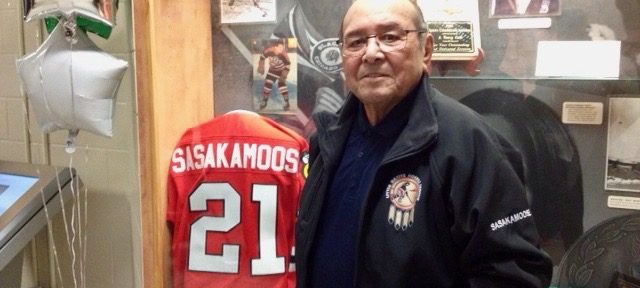

Fred Sasakamoose, left, talks with Chicago Blackhawks captain Alexei Zhamnov after a ceremonial face-off.

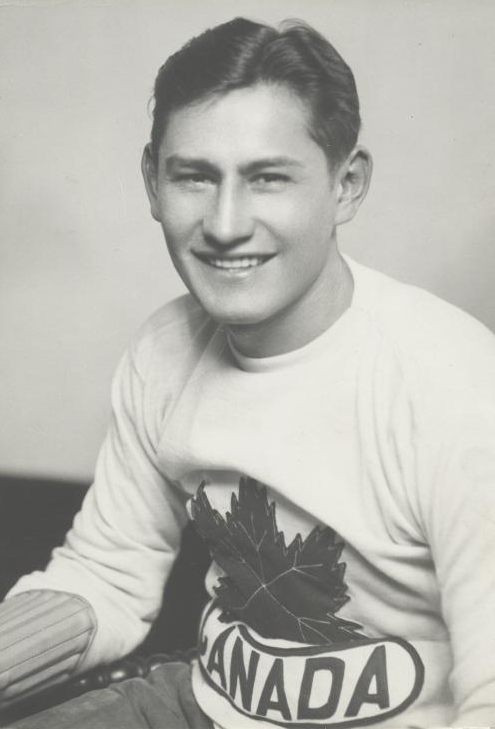

Fred Sasakamoose was born on Christmas Day, 1933 in the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation. When he was six years old, he and his brother Frank were taken from their parents by Indian agents from the Canadian government and driven with 30 other children to the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake more than 100 kilometres away.

Saskamoose found a love of hockey at the residential school and one of the priests, Father Georges Roussel, helped hone his skill. He also suffered horrible abuse and recounted being raped as a young boy during a Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s community hearing in Prince Albert.

Despite what he suffered through as a child, Sasakamoose excelled as a hockey player and reached the National Hockey League as a 19-year-old in 1953 with the Chicago Black Hawks. In doing so, Sasakamoose became the first Indigenous person with Treaty status to play in the NHL.

Sasakamoose would spend 35 years as a Band Councillor of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, six as Chief. He worked to give back to his community and build and develop minor hockey and other sports there.

There is no one better to share Fred’s story than Fred himself. Before he passed away on November 20, 2020, he completed his biography Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player. It is an important book and in writing it Fred said:

And I hope by sharing my story now, non-Indigenous readers might have a better understanding of the hurdles we have to overcome to succeed.

I hope by telling my people about the vision of my grandfather Alexan, they will see how their own belief in the future can strengthen those around them.

I hope by telling them about the friendship of men like Ray, like Dave, like Jerry, about the selflessness and generosity of people like George, they will see that there is goodness in the outside world too.

And finally, I hope my story reminds my people that while it might not be a world made for us, it’s a world we can make better by being proud of who we are and where we come from.

— Fred Sasakamoose, excerpt from Call Me Indian.

Bryan Trottier, six-time Stanley Cup champion and one of the greatest hockey players to ever come out of Saskatchewan, penned a first-person essay on his experiences as an Indigenous hockey player.

SSHF inductees like Sasakamoose, Tony Cote, David Greyeyes and Claude Petit also made considerable contributions to their communities after their sporting careers were over.

Tony Cote

Cote was a residential school survivor and was instrumental in creating the Saskatchewan First Nations Summer and Winter Games in 1974 which are now known as the Tony Cote Summer and Winter Games. He was also elected Chief of Cote First Nation in 1970 and created numerous athletic opportunities for Indigenous youth while also dedicating his time to coaching.

Petit founded the Western Canadian Native Minor Hockey Championships and was a boxing coach, referee and administrator after he hung up his gloves after an impressive career. As a boxer, Petit was a five-time Canadian Army heavyweight boxing champion and the only Canadian to win the British Army Heavyweight Boxing Championship.

Greyeyes is also a residential school survivor who became a Lieutenant in the Canadian Army during the Second World War and was one of the best soccer players in the province during his career, representing Saskatchewan in games against some of the best teams from England. After his athletic career, he became a public servant and became the first Indigenous person to be a director of the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs.

Petit, Sasakamoose and Greyeyes each became a member of the Order of Canada. Petit, Greyeyes and Cote also received the Saskatchewan Order of Merit for their contributions to their communities and all three were also veterans who served in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Kenneth Moore

In addition to the individual Indigenous inductees, the SSHF also has inductees who were members of an inducted team.

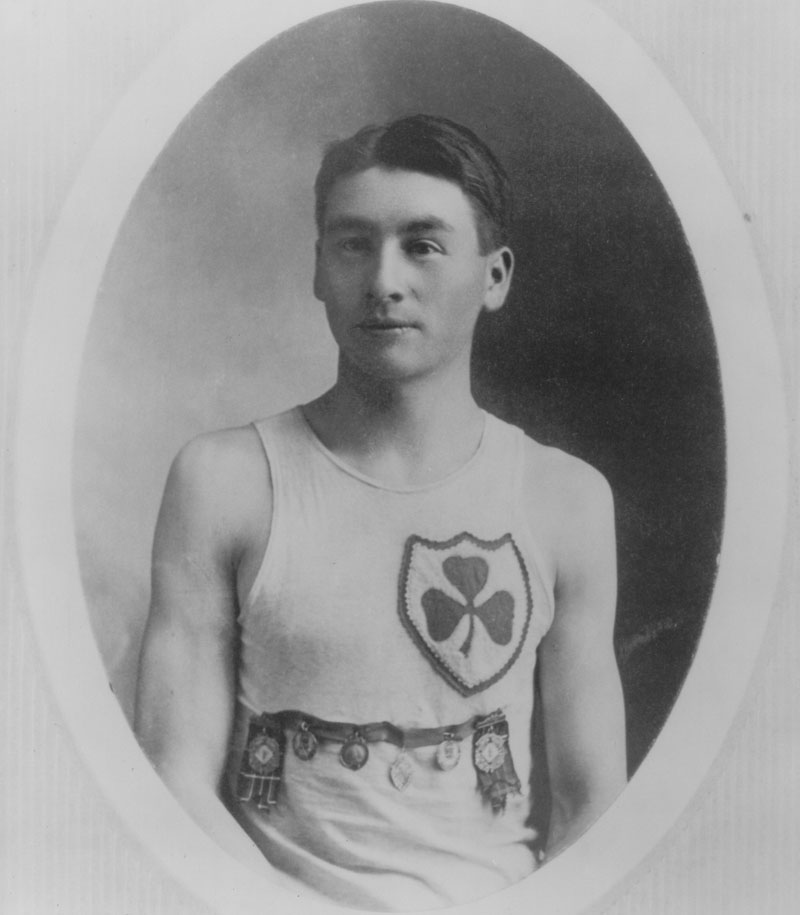

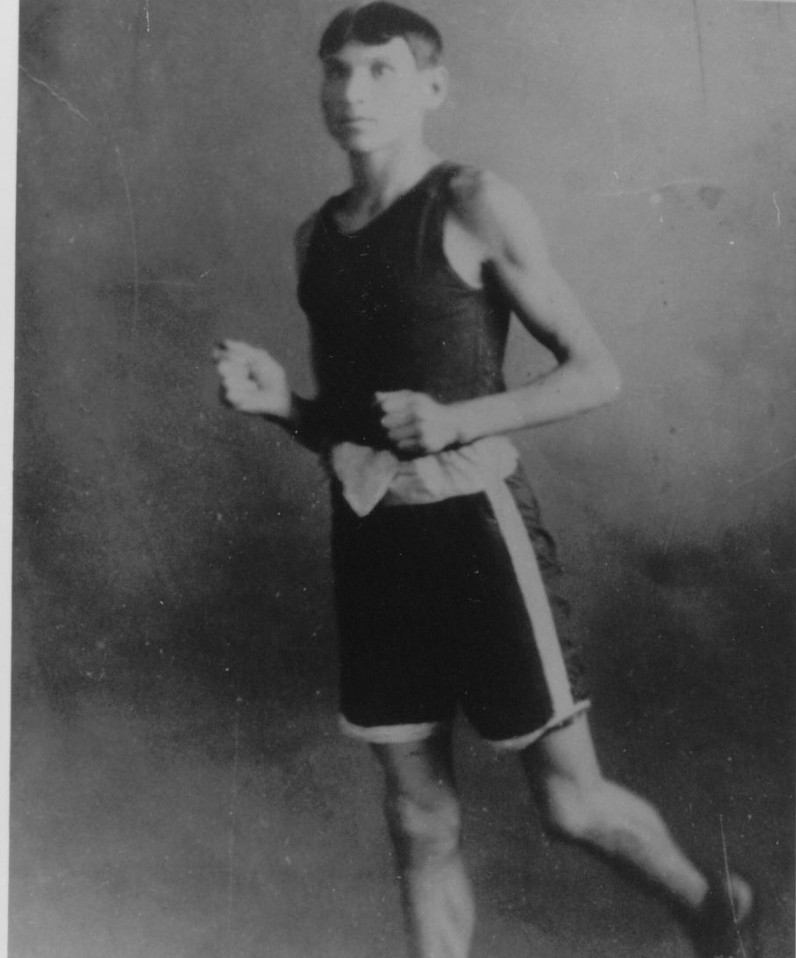

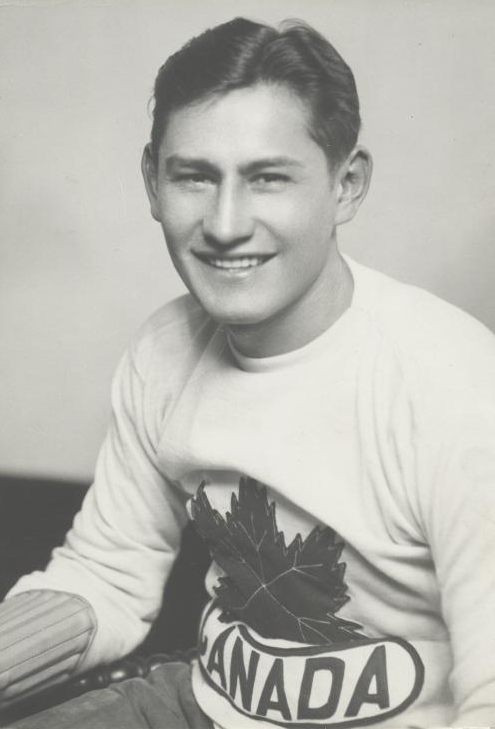

One of those is Kenneth Moore who was inducted as a member of the 1930 Regina Pats hockey team that won the Memorial Cup. Moore is also the first Indigenous athlete to win an Olympic gold medal.

Moore was from the Peepeekisis First Nation and was the third of eight kids born in 1910. One biographer reports that Moore’s two older brothers died while attending a Residential School. Following that tragedy, the family moved from Balcarres to Regina.

A gifted multi-sport athlete, he starred as a right winger on the Regina Pats junior hockey team. In 1930, the Pats met the West Toronto Nationals in the national junior final. The Pats won the first game 3-1 and after trailing 2-0 in Game 2, “Smiling” Ken Moore – as the Regina Leader-Post described him – took a pass in the slot and slid it home with 40 seconds left in the third period to give the Pats a 3-2 and their third Memorial Cup in six years. He also attended Campion College and Regina College on a scholarship where he captained the hockey and rugby teams.

He joined the Winnipeg Hockey Club and they would go on to beat the Hamilton Tigers in two straight games to claim the 1931 Allan Cup, the national amateur hockey championship. As Allan Cup champions, Winnipeg also earned the right to represent Canada at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid, New York. Canada won five games and tied one to earn their fourth straight Olympic gold medal in hockey. Moore scored one goal in the tournament as Canada won Olympic gold.

Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame recently launched their Indigenous Heroes educational website that features Boungonje, Decoteau and Trottier and many other Canadian Indigenous sporting legends.

These are but a few of the many stories of both Indigenous athletes in Saskatchewan and also the experience of residential school survivors.

Following the discovery of 751 unmarked graves at the Marieval Indian Residential School at the current site of Cowessess First Nation — along with seven other sites in Canada to date — the importance of learning about the history and impact of residential schools has only increased.

The staff at the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame acknowledges the impact and enduring legacy of the residential school system in Canada. Today we reflect on that history, but each day we are dedicated to listening to and learning from the First Nations as we commit to moving towards reconciliation.

To that end, here are some other useful resources to learn more about the history of the residential school system and the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

The film We Were Children is available from CBC Gem and is available for rent from the National Film Board of Canada.

Here is a list of 150 acts of reconciliation penned for Canada’s 150th anniversary.

Learn the history behind Phyllis Webstad’s residential school experience which led to the creation of “Orange Shirt Day”.

The University of Alberta is offering Indigenous Canada, a free, 12-lesson Massive Open Online Course from their Faculty of Native Studies.

You can also read the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls To Action and the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation offers numerous resources.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is located on Treaty 4 land which is situated on the territory of the Anihšināpēk (Saulteaux), Dakota, Lakota, Nakota (Assiniboine), Nêhiyawak (Cree), and the homeland of the Métis Nation.

The SSHF’s mandate is to share the sport history of the land that is also located on Treaties 2, 5, 6, 8 and 10 territory. Those territories are also the traditional lands of the Anihšināpēk (Saulteaux), Dakota, Denesuline (Dene/Chipewyan), Lakota, Nakota (Assiniboine), Nêhiyawak (Cree), and the homeland of the Métis Nation.