The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation on September 30 honours the children who never came home and the survivors of the residential school system as well as their families and communities.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame will be closed on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation as we pause to reflect on the impact and enduring legacy of the residential school system in Canada as we commit to moving toward reconciliation.

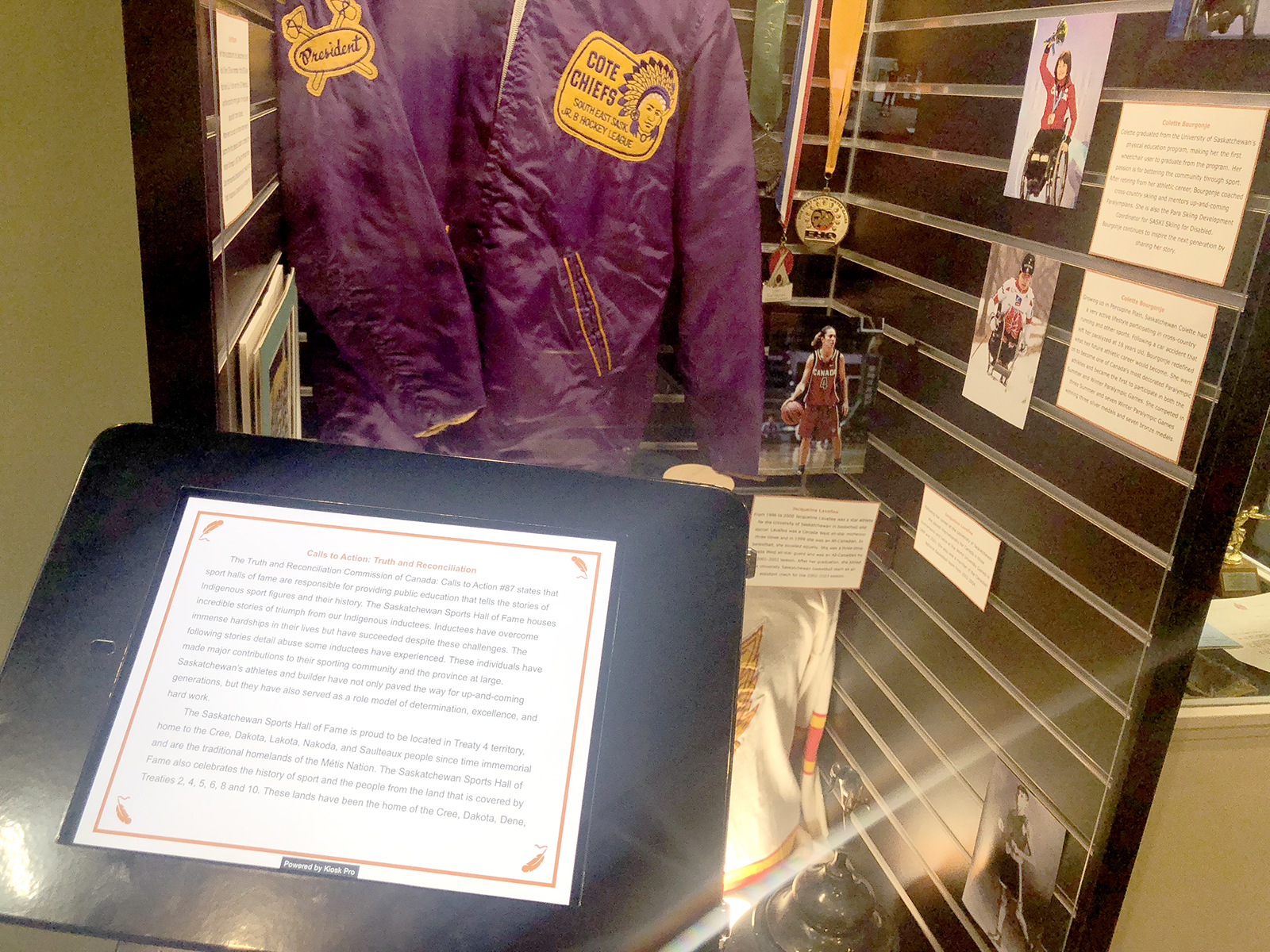

The National Day for Truth and Reconciliation was established in response to Call to Action 80 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada which called for a federal statutory day of commemoration of the history and ongoing impact of the residential school system. At the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame, we are committed to following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 87th Call to Action that calls on sports halls of fame to provide public education that tells the national story of Aboriginal athletes in history.

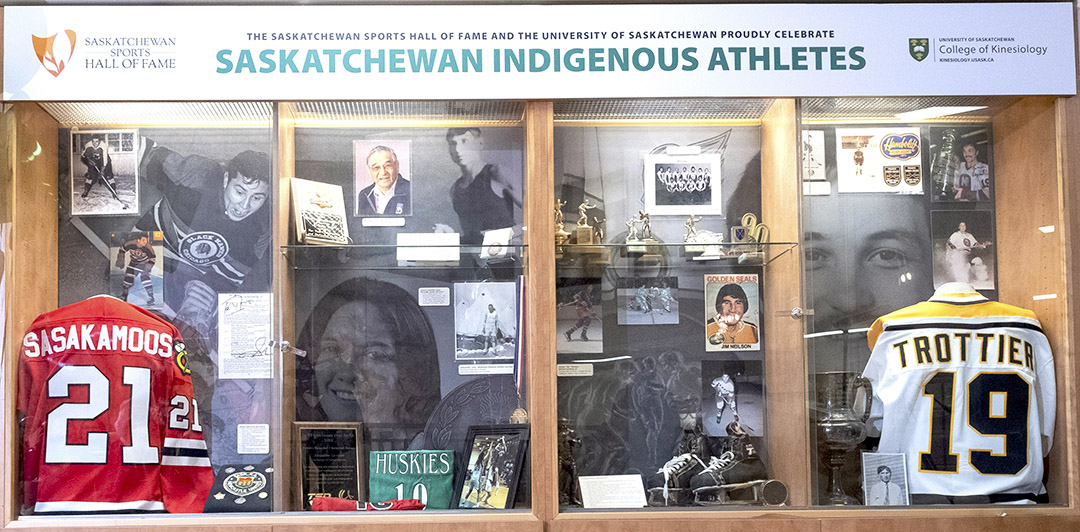

The Hall of Fame now offers a permanent exhibit called Truth and Reconciliation: Calls To Action which features artifacts and displays celebrating Saskatchewan indigenous sporting achievement. It also features a dedicated tablet that tells their stories in detail. The SSHF also has a display case and video kiosk celebrating Saskatchewan Indigenous athletes and their achievements, which is permanently displayed in the Physical Activity Complex at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Kinesiology in Saskatoon.

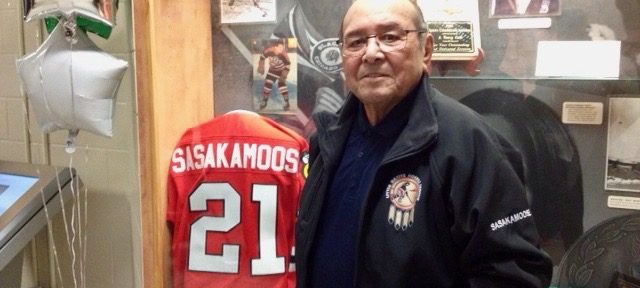

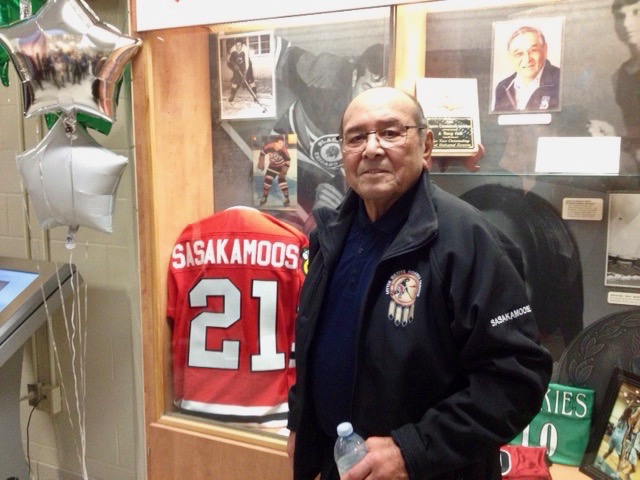

Fred Sasakamoose at the opening of the SSHF’s Indigenous sport exhibit at the University of Saskatchewan.

David Stobbe/StobbePhoto.ca

We continue to offer our Indigenous Legacies in Sport outreach program to classrooms across the province where we share the vital role that Indigenous athletes and builders have played in Saskatchewan’s sport and cultural history. This past year, through a partnership with Nature Saskatchewan, participants in the SSHF’s School’s Out program also learned about and played traditional Indigenous games.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame currently has 11 individual athletes who identify as Indigenous and have been inducted. Those athletes and builders are: Paul Acoose, Colette Bourgonje, Tony Cote, Alex Decoteau, David Greyeyes, Jacqueline Lavallee, Ray Mitsuing, Jim Neilson, Claude Petit, Fred Sasakamoose, and Bryan Trottier.

In addition to the individual Indigenous inductees, there are also Indigenous inductees who were enshrined in the Hall of Fame as members of a championship team.

There are several inductees in the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame who were victims of the residential school system.

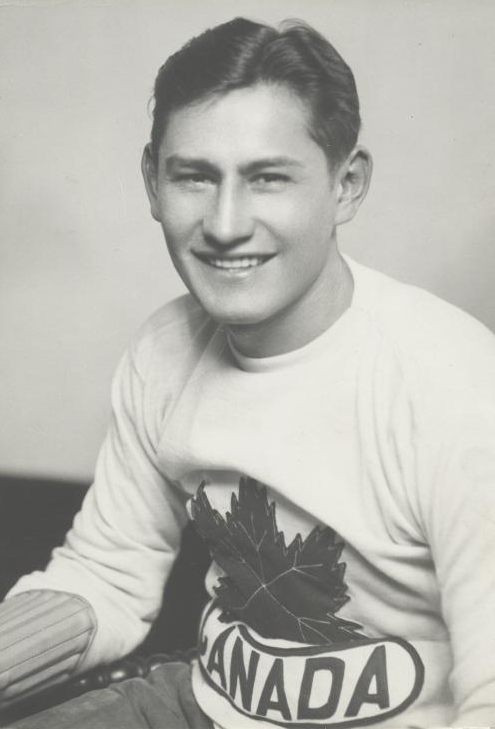

Fred Sasakamoose

Fred Sasakamoose wrote vividly and candidly about his experience at the residential school in his 2021 autobiography Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player.

When he was six years old, he and his brother Frank were taken from their parents by Indian agents from the Canadian government and driven with 30 other children to the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake more than 100 kilometres away from his home on the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation. He suffered horrible abuse at the school as well as dehumanizing treatment along with the other students.

Despite all that he suffered as a child, Sasakamoose starred as a junior player in Moose Jaw being named the Most Valuable Player in the Western Canadian Junior Hockey League in 1953-54. He reached the National Hockey League as a 19-year-old in 1953 with the Chicago Black Hawks. In doing so, Sasakamoose became the first Indigenous person with Treaty status to play in the NHL.

Sasakamoose also spent 35 years as a Band Councillor of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, including six as Chief. He worked to give back to his community and build and develop minor hockey and other sports there.

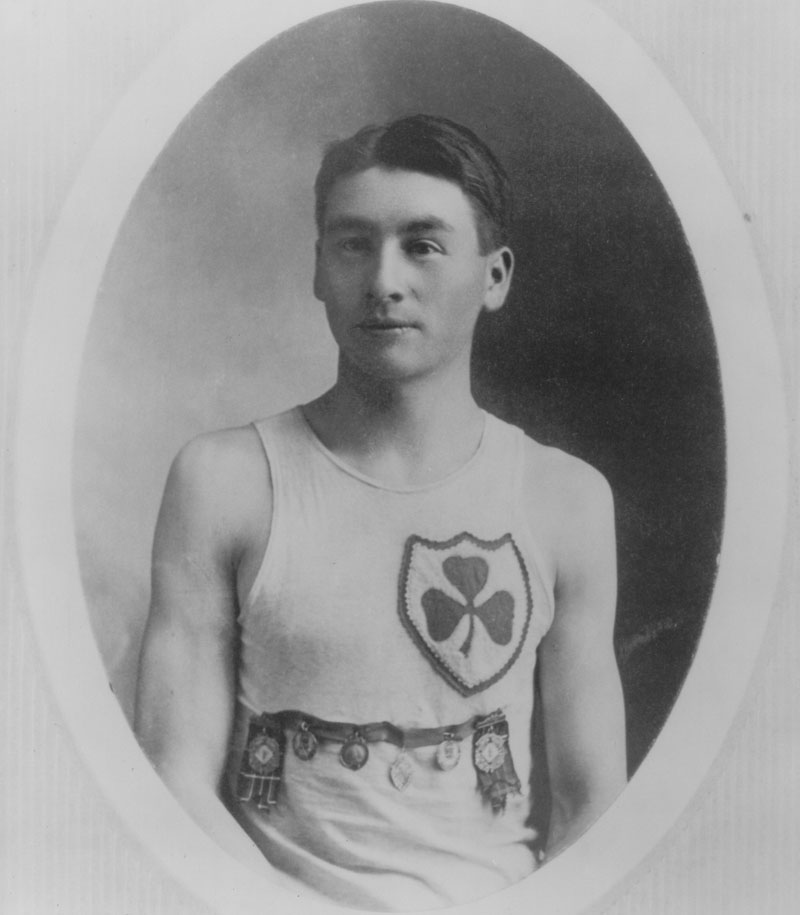

Ken Moore

Kenneth Moore, from the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, was inducted into the SSHF as a member of the 1930 Regina Pats hockey team that won the Memorial Cup. Moore is also the first Indigenous Canadian athlete to win an Olympic gold medal.

Moore was the third of eight siblings. His two older brothers had been taken to the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba – more than 300 kilometres away. They both died after being sent to the residential school. Kenneth would have been forced to attend the school when he turned seven. Instead, the Moore family fled the Peepeekisis First Nation in the middle of the night.

These stories from two of our inductees are just a small example of the countless ways the residential school system has impacted the Indigenous population.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is proud to be physically located in Treaty 4 territory, which is home to the Cree, Dakota, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame also celebrates the history of sport and the people from the land that is covered by Treaties 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10. These lands have been the home of the Cree, Dakota, Dene, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation.

Our nomination process is open to the public and if you believe you know of an athlete, builder or team that deserves inclusion in the Hall of Fame we invite you to nominate them. You can learn more about that process here.