February is Indigenous Storytelling Month in Saskatchewan. To celebrate this month, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is sharing some of the stories of some of the pioneering Indigenous athletes in the province – in their own words as much as possible.

Tony Cote was inducted into the SSHF as a builder in 2011. He was first elected as Chief of the Cote First Nation in 1970. In 1974 he was instrumental in the creation of the Saskatchewan First Nations Summer Games. They would grow to include a Winter Games and now both the Summer and Winter Games bear his name.

In an article from 2014 in the Regina Leader-Post, Cote described what motivated him to create the first Saskatchewan First Nations Summer Games.

Tony Cote

“There wasn’t too much sports and recreation on any given reserve (when he started the provincial Games). I thought if we initiated some kind of Summer Games we would get the interest of the young people to participate with the other bands across Saskatchewan. The response was very, very good. I think the first year we attracted 500 athletes. The last one we had in Prince Albert (in 2013) I think we had 3,500 athletes. The participation of our young people has really grown tremendously.

“As a result, we always develop some very good athletes.

“One of these days we’re going to have a number of our own athletes participate in the Olympics. That was my vision to begin with. It’s slowly coming.”

Even for those athletes who don’t end up on the world’s stage, taking part in the Tony Cote Games or the North American Indigenous Games can have a lifelong impact.

“It opens (people’s) eyes. The atmosphere is terrific. You can tell they’re proud and they want to compete. As a result, a lot of the former athletes that participated 10, 12 or even 20 years ago, those are our recreation leaders now. Not only recreation leaders but some of them have become leaders of their communities in the capacity of chief and councillors.

“When I first came home to start sports and recreation (in Saskatchewan) there was absolutely nothing. All our kids were just getting into trouble. When we started training them (the outlook improved).

“We’ve come a long ways.”

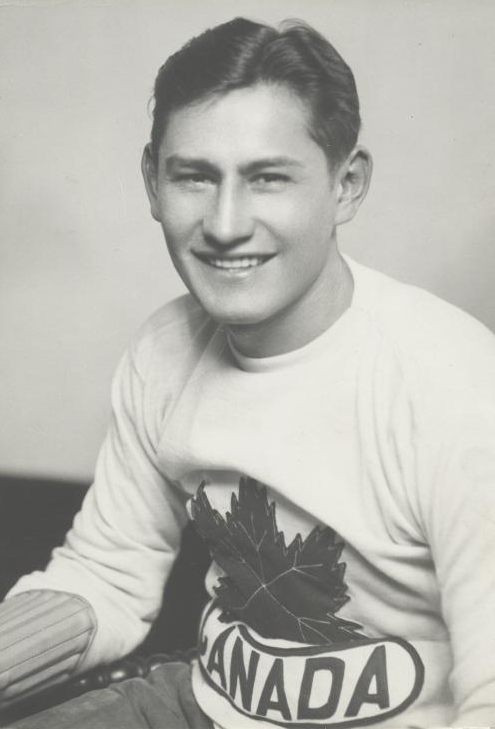

Ken Moore

Ken Moore was the first Indigenous person to win a gold medal for Canada when he was part of the 1932 men’s hockey team that won gold in Lake Placid in the United States. Moore has been inducted into the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame as a member of the 1930 Memorial Cup champion Regina Pats team.

Before those great feats though, Moore and his family escaped their home in the Peepeekeesis Cree Nation and avoided the Indian agent to start a new life and keep any more of their children from being forced to attend Residential School. The Moores’ two oldest sons both died at the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba.

Moore’s granddaughter, Jennifer Moore Rattray, helps tell his incredible story here.

Alex Decoteau died during the Second Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 during the First World War. Though his life was cut tragically short, the distance runner from Red Pheasant First Nation achieved so much. He was the first athlete born in what is now Saskatchewan to compete at the Olympics. He is also the first Indigenous person to be a police officer in Canada.

Independent Indigenous publication Windspeaker.com in Edmonton shared Alex’s story here.

Jim Neilson moved to an orphanage in Prince Albert at the age of five and he become one of the best defencemen in the National Hockey League in the 1970s and played more than 1,000 games in the league. You can read more about his inspiring story here.

Fred Sasakamoose, left, shakes hands with Chicago Blackhawks captain Alexei Zhamnov.

Fred Sasakamoose was taken from his family on the Ahtahkakoop Cree First Nation and sent to St. Michael’s Residential School in Duck Lake. There Sasakamoose suffered terrible abuse that he detailed in the Truth & Reconciliation Commission and later in his autobiography.

He returned home at 15 and never wanted to leave. His hockey talents led him to Moose Jaw – where two weeks into his stay he tried to walk the 400 km home – where he became the Most Valuable Player in the Western Canadian Junior Hockey League in 1953-54. Immediately at the end of the season, the 20-year-old reported to the NHL’s Chicago Black Hawks where he would play 11 games. Despite his talent and early success, the pull of coming home never left.

“I wanted to go home all the time,” Sasakamoose said in this article from 2018. “You’re no longer 500 miles away — you are 5,000 miles away. It didn’t matter about money, glory… It didn’t matter. I didn’t want that. I wanted home.”

Paul Acoose was Nakawē (Saulteaux) from the Zagime Anishinabek (previously known as the Sakimay First Nation) and was born in 1885. In his first professional race, Acoose ran 15 miles in a world-record time of one hour, 22 minutes and 22 seconds and beat famed English runner Fred Appleby, a former world record holder and 1908 Olympic marathon runner. Acoose’s record-breaking time earned him the title of world champion.

Acoose’s rapid rise to success was met with adversity almost immediately. Appleby and Acoose met in a rematch in Winnipeg where gamblers who had bet on Appleby were suspected of throwing thumbtacks on the indoor track. The tacks did not affect Appleby in his thick rubber-soled shoes, but easily penetrated Acoose’s moccasins and into his feet. Acoose had a half-lap lead when the tacks were thrown onto the track. He pulled a tack out of his foot and carried on – running two more miles in bare feet – before stepping on more tacks and was unable to finish the race.

Acoose went on to beat famed Onondaga runner Tom Longboat in 1910. Despite only being 24 years old, Acoose retired from competitive racing and settled in Zagime Anishinabek with his wife Madeline where they raised nine children and farmed. He never drove a car and continued to job into his 60s. Even in his late 70s would walk up to 10 kilometers to visit family and friends.

Bryan Trottier won six Stanley Cups and was a cornerstone of the New York Islanders dynasty. The Hockey Hall of Famer wrote on the NHL website about his youth in Val Marie.

“I don’t know how big an inspiration I am for indigenous children, but I want to wear it with all my might. There’s a certain pride I think we all have in where and how we grow up and our heritage. There’s a lot of variety in First Nation; it’s a very diverse group. Some of them feel self-conscious about the blend they have, that maybe they’re not 100 percent First Nation. But they have the bloodlines, and they’re very creative and they’re very athletic and talented. They all have the ability to make a difference, and I tell them it’s OK to be homesick but to remember it takes courage to live your dreams.”