The summer of 2020 has featured numerous postponements and cancellations across the sporting world — none bigger than the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics which were pushed back a year.

At the same time, the nexus of sports and politics has intersected at a level that has rarely been seen before.

Forty years ago, however, Saskatoon’s Diane Jones Konihowski experienced both political fallout and the loss of a chance to compete at the Olympics at the same time when she became the centre of controversy after speaking out following Canada’s decision to join the boycott of the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympic Games.

Jones Konihowski was one of the faces of amateur sport in Canada and had the endorsements, commercials and name recognition that came with it. That public goodwill evaporated seemingly overnight following her criticisms of the boycott at the height of the Cold War which led to hate mail and death threats directed at her, along with her family and friends.

“I was the only one speaking out against it, everyone else got sucked in,” Jones Konihowski said recently from her home in Calgary.

For Jones Konihowski, it would have been her third Games competing as a pentathlete, but it also constituted her last — and best — shot at an Olympic medal.

“I was alone in speaking out as far as I remember. It was easy for me to speak out because I was out of the country and I wasn’t being brainwashed. I could think very, very clearly and look at the scenario and think ‘this is very wrong on so many levels.’ I was able to articulate that. It took many years before people would come to me and say, ‘you know you were right,’” Jones Konihowski said. “To this day — and it was 40 years ago — people still come up to me and say that was so wrong at that time. Nobody had the guts. I can’t remember anyone else chastising the Canadian Olympic Association for their decision.

“It’s interesting this year that we were the first in the world to say that we’re not going (to the Tokyo Olympics) because of COVID. We led the world in saying it’s not safe to go. Then Australia fell in and Great Britain came and then the Games were postponed.”

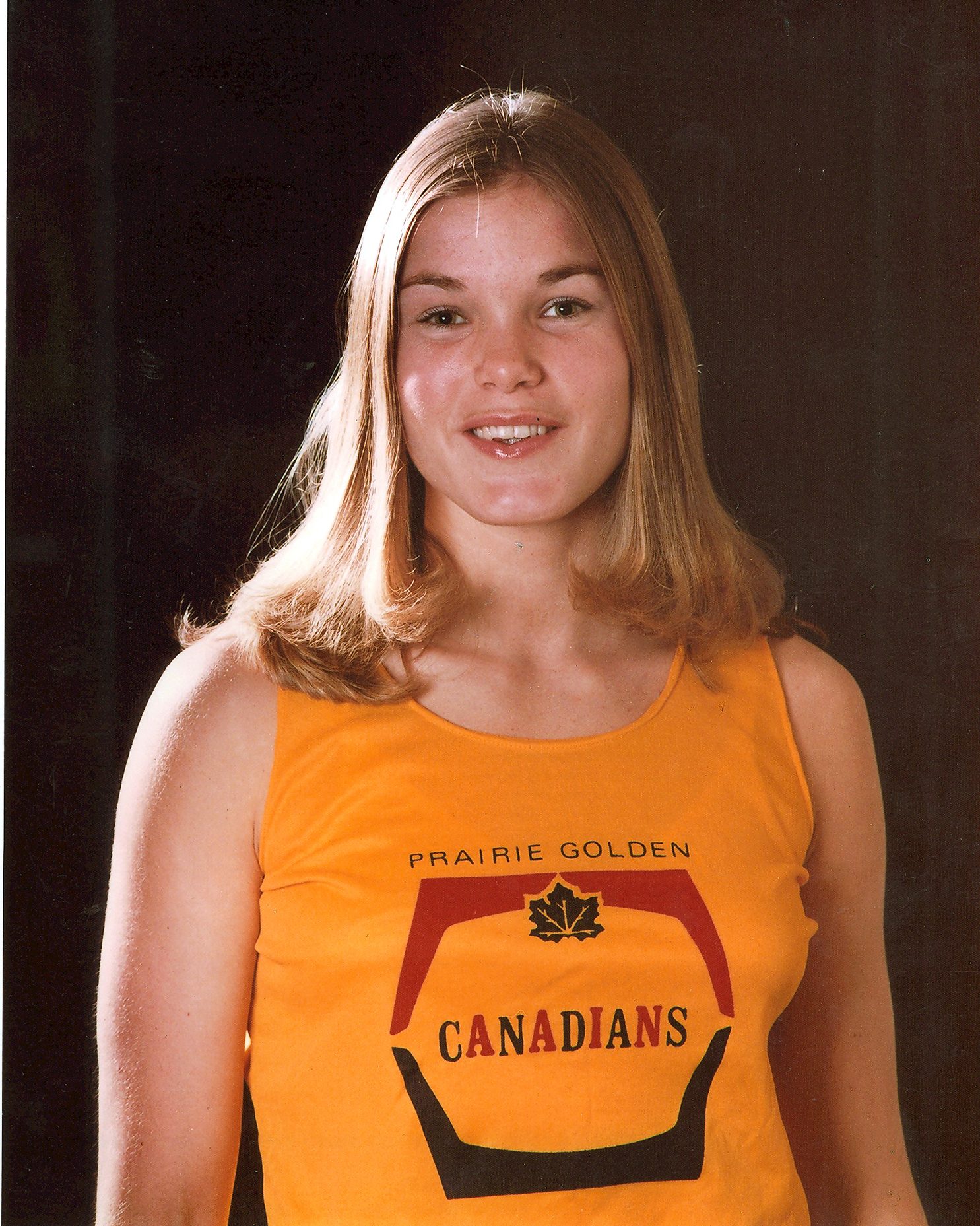

Jones Konihowski was raised in Saskatoon and attended Aden Bowman Collegiate and the University of Saskatchewan where she excelled in track and field and also as a volleyball player with the Huskies. An exceptional all-around athlete, she was also a promising gymnast in her youth and was coached by Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame inductee Chuck Sebestyen before she out-grew the sport.

“Looking back I really lucked out with some amazing Phys. Ed. teachers and sport coaches. They just motivated me to love what I was doing,” Jones Konihowksi said. “Two of my coaches were Olympic coaches. Bob Adams was my first coach in track and field and he was obviously an Olympic decathlete and he was one of the Olympic coaches in 1964. Chuck Sebestyen, one of my gymnastic coaches, was also (an Olympic) gymnastics coach in 1964.

“I just lucked-out meeting all of these people in my life. They were there for me to really nurture and push me to be a better athlete.”

Having excelled at multiple sports and being naturally competitive, it only made sense that Jones Konihowski would excel at the pentathlon which featured five events: shot put, high jump, long jump, the 200-metre run and the 100m hurdles.

She was 21 years old when she made her Olympic debut in Berlin where she finished in a very respectable 10th place.

“It was fabulous. There’s nothing like the Olympic Games. I don’t care what anyone else says,” Jones Konihowski said.

The joy of her first Olympics turned tragic when 11 members of the Israeli delegation were kidnapped from the Olympic Village, held hostage and ultimately killed by terrorists.

Jones Konihowski had just completed competition on September 5 when the pre-dawn attack occurred and was headed into the city with fellow Canadian track athlete Joyce Sadowick to meet up with another Canadian to do some sightseeing. When they woke up in the early hours there was already an eerie silence in the Athletes Village that tipped them off that something was wrong. As soon as they left the Village they were swarmed by reporters looking for information on the breaking story.

Diane Jones Konihowski competing in the high jump while at the University of Saskatchewan. photo courtesy the University of Saskatchewan.

“For me, I was touched by it because the day before I was training in hurdles with Esther Roth, who was a hurdler from Israel, and after training we went to lunch and she said ‘why don’t you come over and have lunch with us.’ So I had lunch with a bunch of wrestlers and basically, all of those guys were dead the next day,” Jones Konihowski said.

Despite being an Olympic pentathlete, Jones Konihowski was also still playing volleyball at the U of S, but a serious ankle injury at the end of the volleyball season required surgery and hurt her chances at the 1974 Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand where she finished sixth.

Fully healthy, she won the pentathlon gold medal at the 1975 Pan American Games in Mexico City and expectations were high coming home for the 1976 Montreal Olympics.

She had an endorsement deal with Canadian apparel company Penmans and appeared in commercials with Montreal Expos star Gary Carter, Olympic skier Nancy Greene, and hockey broadcaster Howie Meeker.

“Montreal was a huge learning experience. Because I was a media darling, they loved me all through the 70s — I was tall, long legs, long blonde hair and I was successful — I got a lot of media attention,” Jones Konihowski said.

Jones Konihowski was training in Santa Barbra, California in the lead-up to the ’76 Games, but was back in Canada every other weekend promoting the Games. She did a cross-country tour as the “coin girl” with André Ouellet, the Postmaster General at the time. Even when she arrived in Montreal, she was already kicking herself for disrupting her training schedule so significantly.

“The frustrating thing for me in ’76 was I could have got a medal. All the way through the competition I’m just thinking ‘damnit, if I was really at my peak I really could have got a medal,’” said Jones Konihowski who finished sixth in the pentathlon and also seventh in the long jump.

“I came out of Montreal really ticked off because I blew it. I realistically could have got an Olympic medal, but you learn. At the end of the day, it’s not about the hardware. I’ve always said that. We only learn from those times when you fail, you underperform and put in a disappointing performance. It’s the only time you learn. You don’t learn from your successes.”

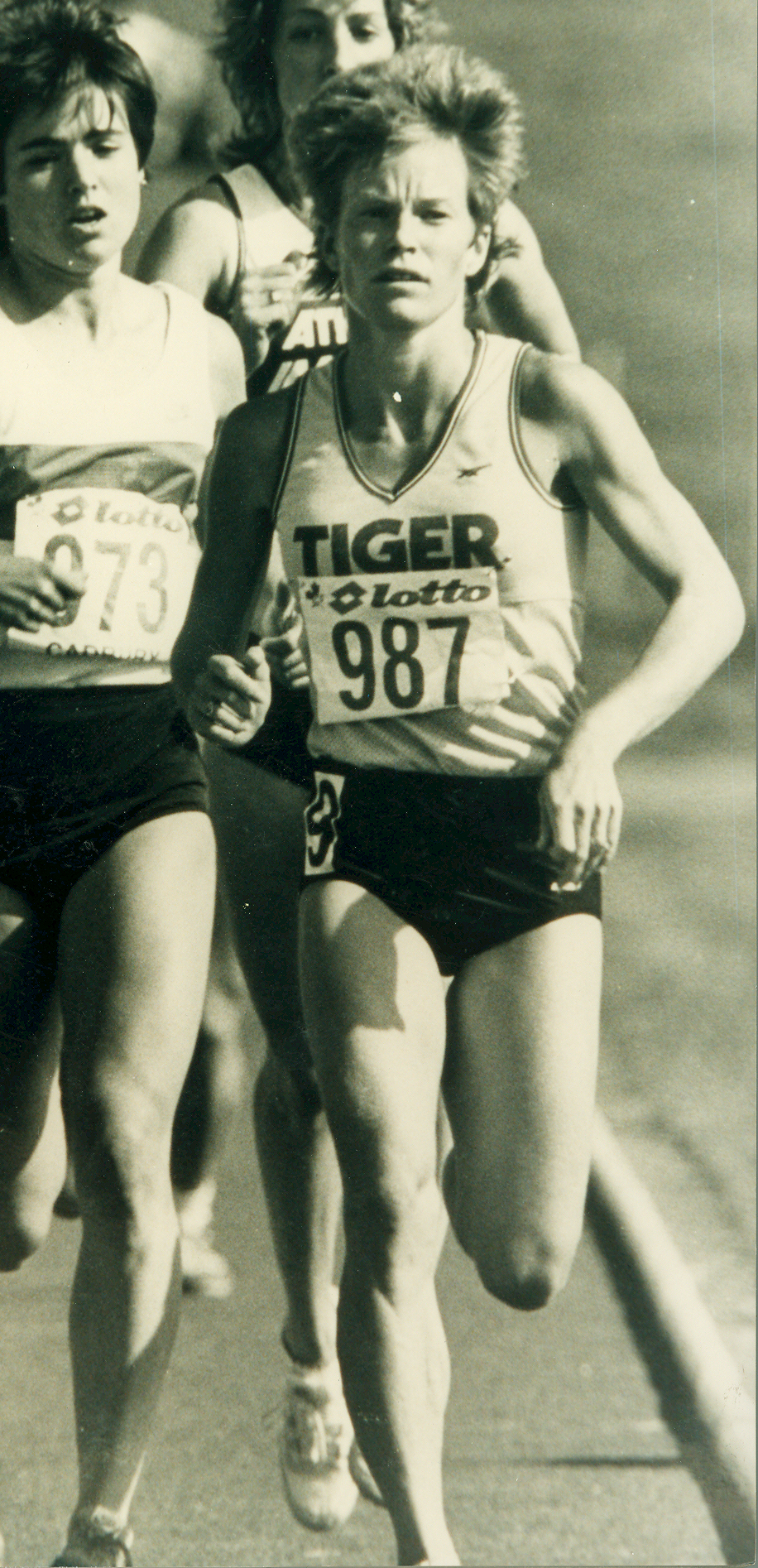

She competed under her maiden name as Diane Jones in ’72 and ’76 but married fellow SSHF member and former Huskies track athlete John Konihowski in 1977 while he was a member of the Canadian Football League’s Edmonton Eskimos. While making Edmonton their home, the 1978 Commonwealth Games would be in the Alberta capital and once again Jones Konihowski would be one of the faces of the event. She was the Queen’s Baton Final Runner – the Commonwealth Games equivalent to being the torchbearer at the opening ceremonies. However, nothing was going to distract Jones Konihowski from her goal. She won the pentathlon in a games record score. A year later she repeated as Pan American Games champion in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

“Going into ’78 – Edmonton, hometown, really important to do well – I just said a lot of no’s. I didn’t get caught up in that and I did very well. Not only did I win the gold medal in Edmonton, but more importantly it was with a score that put me No. 1 in the world,” she said. “That told me that I’m on track to get on the podium in Moscow, two years later. I was very, very focused.

“(The Pan American Games) was a really good performance — Canadian record, Pan American Games record, the whole bit — so I thought OK good, we’re right on track here.”

Still, she wanted to ensure she was free of distractions. Years earlier she had invited Karen Page, a pentathlete from New Zealand, to come up to Saskatoon to train with her coach at the U of S, Lyle Sanderson (who is also an SSHF inductee). After spending Christmas of 1979 at home, Diane, John, and Sanderson and his family all moved down to Auckland, New Zealand to train with Page and get laser-focused on Moscow with no distractions.

The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December of 1979 to start the Soviet-Afghan War and in January of 1980, U.S. President Jimmy Carter threatened to boycott the Moscow Olympics is the Soviets didn’t pull out of Afghanistan by February 20, 1980. Later that month, Canadian Prime Minister Joe Clark also threatened a boycott. Not coincidentally, the Lake Placid Winter Olympics would take place in February of 1980 with the Soviets competing in the U.S. Those Games concluded four days after Carter’s ultimatum.

On April 22, 1980 – a date Jones Konihowski can recall with ease – with the U.S. State Secretary due in Ottawa the next day, the new Pierre Trudeau government formally backed the boycott.

In New Zealand, Jones Konihowski found out that her Olympic medal dream was dashed when a reporter at an Edmonton radio station called her. She didn’t hold back in criticizing the decision.

“I was very disappointed when I got the call on April 23,” Jones Konihowski said. “Of course I had not watched any media from back home, I had not read a thing. So I was clear-headed and not brainwashed.

“I was saying it was wrong on a number of levels. One, it’s no surprise to world leaders that Russia has invaded Afghanistan, come on, give me a break here. We’re still sending wheat to Russia; we’re still trading with them. President Carter could have made a much stronger statement to Russia by denying them to come to his Games in February, but he waited until the end of their Games to announce a summer boycott. That’s wrong. On all levels, it’s wrong.”

The boycott ended up being widespread, but at different levels of involvement. China, Japan and West Germany were also among the countries that didn’t send any athletes. Some western nations sent smaller squads and some individual athletes opted not to compete. Some nations — France, Spain, and Italy notably — attended but competed under the Olympic flag and did not attend the opening ceremonies.

“My greatest disappointment is really that the Canadian Olympic Association at that time went with the government’s decision,” Jones Konihowski said. “I can see the government following Carter. That’s OK. But the Canadian Olympic Association I felt let down the athletes and coaches by following suit and declaring that they were going to stay home as well. Meanwhile Iron Lady (Margaret) Thatcher said no and the British Olympic Association said ‘we’re going.’ So they went. If you can say no to Iron Lady Thatcher, why can’t we say no to Pierre Trudeau?”

Back home, Jones Konihowski’s comments were not well received. To put it mildly.

“My mom was phoning me ‘Oh my God, everyone is calling you a Communist. Can you shut up.’ All of that kind of stuff,” she said. “The two girls in our apartment in Edmonton were getting horrible phone calls. So we basically told them to not answer the phone.

“Even Karen in New Zealand was getting bomb threats, her parents were going nuts.

“It was a really, really crazy time. Canadians mostly love to complain, but they never act on it. It was a really contentious time.”

Jones Konihowski also quickly got a call from her sponsor in Toronto.

“They said ‘Unless you retract what you’re saying, I can’t support you any longer,’” she recalled. “I said ‘You know Jamie, that’s fine. Put your money with another athlete, but I really believe strongly in this. This is wrong. This has nothing to do with Russia invading Afghanistan. Do you think Russia is going to pull out?’”

They returned to Canada in May and the mood of her detractors hadn’t calmed any.

“John didn’t let me read any of the hate mail. And there was a lot of it,” Jones Konihowski recalled. “The Edmonton Eskimos, their lines were ringing off the hook, ‘how can you hire the husband of a Communist?’ John got it on the football field as well. He was called a ‘Commie’, which is interesting. (Edmonton head coach) Hugh Campbell stood up for me. The Edmonton Eskimos organization supported me, which was good, and John, which was awesome.

“I got a few positive letters, but in the media, I was lambasted by many of my friends. It was a really difficult time. I still felt so strongly that it was so wrong. It made no sense that we would be punished for something that is so political.”

Four-time Canadian Olympian Abby Hoffman — Canada’s flag-bearer in Montreal — was a member of the executive council of the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF), track and field’s governing body, and reached out to Jones Konihowski.

“She phoned me and said: ‘I have an invitation for you from the Russian organizing committee to come to the Games,’” Jones Konihowski said. “I didn’t ask her, but I assume that the invitation would have been extended to other athletes and not just me. I said ‘oh Abby, I have to think about this. You wouldn’t believe the death threats we’re getting.’

“I turned it down. I really thought that I wouldn’t get out of this country alive. I kind of feared for my family a little bit. My mom and dad didn’t deserve that. John and the Edmonton Eskimos certainly didn’t deserve that.”

Jones Konihowski instead competed in the Liberty Bell Classic, a track and field event in Philadelphia for athletes who boycotted the Games. She won the pentathlon with ease, but it was cold comfort with the real Games kicking off in Moscow days later.

Soviet athletes swept the medals in the pentathlon with Nadiya Tkachenko — fresh off an 18-month ban after testing positive for steroids — setting a world record in the process.

Two weeks later at the first post-Olympic competition in Germany, Jones Konihowski beat all three Moscow medalists.

1980 Summer Olympics pentathlon champion Nadezhda Tkachenko competing in the shot put portion of the pentathlon at Moscow’s Lenin Stadium. RIA Novosti archive, image #399455 / Yuriy Somov / CC-BY-SA 3.0

“Tkachenko was a druggy and you knew that they weren’t going to test positive at their Games. There was no way,” Jones Konihowski said. “Without (American Jane Frederick) and I there, there was no competition really in the pentathlon and the three Russians won it. I don’t even know what they scored, but it was brutal. Then two weeks later in Germany, I blew them out of the water. They were off their drugs, clearly, and they were just sucking eggs two weeks after the Olympic Games. I’m sorry, that doesn’t sit well with me.”

Tkachenko had finished one place ahead of Jones Konihowski in Berlin and again in Montreal as they continued to improve. Both times Frederick was behind them and in Montreal finished fifth-sixth-seventh. Jones Konihowski hoped that four years on, she, Tkachenko and Frederick would all move up the standings together to share the medals.

“So my dream was that our third and final Olympics… you’d go from 9-10-11 to 5-6-7 to 1-2-3. That was sort of my dream that that was how it would come out,” she said. “It would have been a beautiful story.”

There would be no storybook ending to Jones Konihowski’s great career as she retired in 1983.

“It was maybe six or seven years later that I started wondering what would have happened if I had gone,” Jones Konihowski said.

Twenty years after her criticism of the Canadian Olympic Association, she returned to the Games as Canada’s Chef de Mission for the 2000 Sydney Summer Olympics.

Jones Konihowski has been named to the 2020 class for Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame. She was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1978, was the CEO of KidSport Canada and was a director of the Canadian Olympic Committee.

Diane Jones Konihowski was inducted into the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame in 1980.