June 21 is National Indigenous Peoples Day. In the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 87th Call to Action, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame marks this day by celebrating Indigenous excellence and achievement in sport. In doing so, the SSHF also looks to put a spotlight on the challenges and hardships that the SSHF’s Indigenous inductees overcame in achieving their goals.

The SSHF currently has 11 individual inductees who identify as Indigenous. Each has a unique story, but service to community and success over hardship are common themes with each athlete or builder.

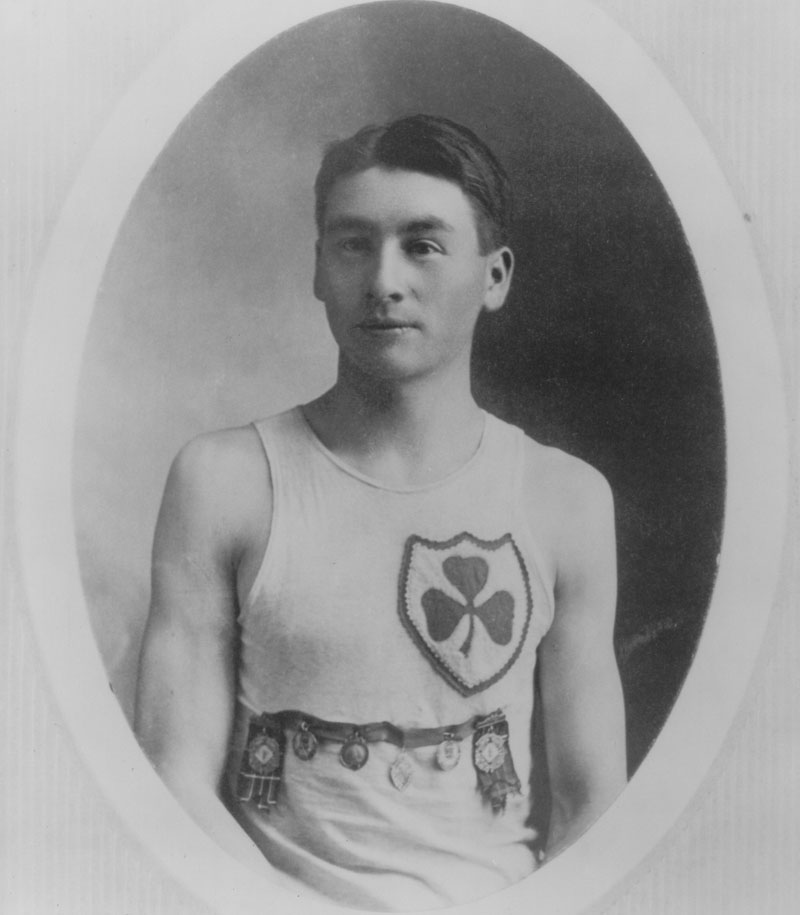

Paul Acoose was from the Zagime Anishinabek (Sakimay) First Nation and came from a long line of distance runners. His competitive career was short, but he set a world record and defeated famed distance runner Tom Longboat before returning home to farm and raise a family.

Colette Bourgonje is a 10-time Paralympian and the first Canadian to compete in both a Summer and Winter Paralympics. Eighteen years after her Paralympic debut she won Canada’s first medal at the 2010 Paralympic Winter Games in Vancouver. There she also received the Whang Youn Dai Achievement Award, which is awarded each Games to a male and female athlete who best exemplifies the spirit of the Games “who prioritizes the promotion of the Paralympic Movement above personal recognition.”

Tony Cote had a lasting impact on the Cote First Nation where he created numerous athletic opportunities for young people. Those athletic opportunities extended across the province when he created the first Saskatchewan First Nations Summer Games in 1974. There is now a distinct Summer and Winter Games and they have both been named after Cote in his honour. Cote became Chief of the Cote First Nation also served during the Korean War.

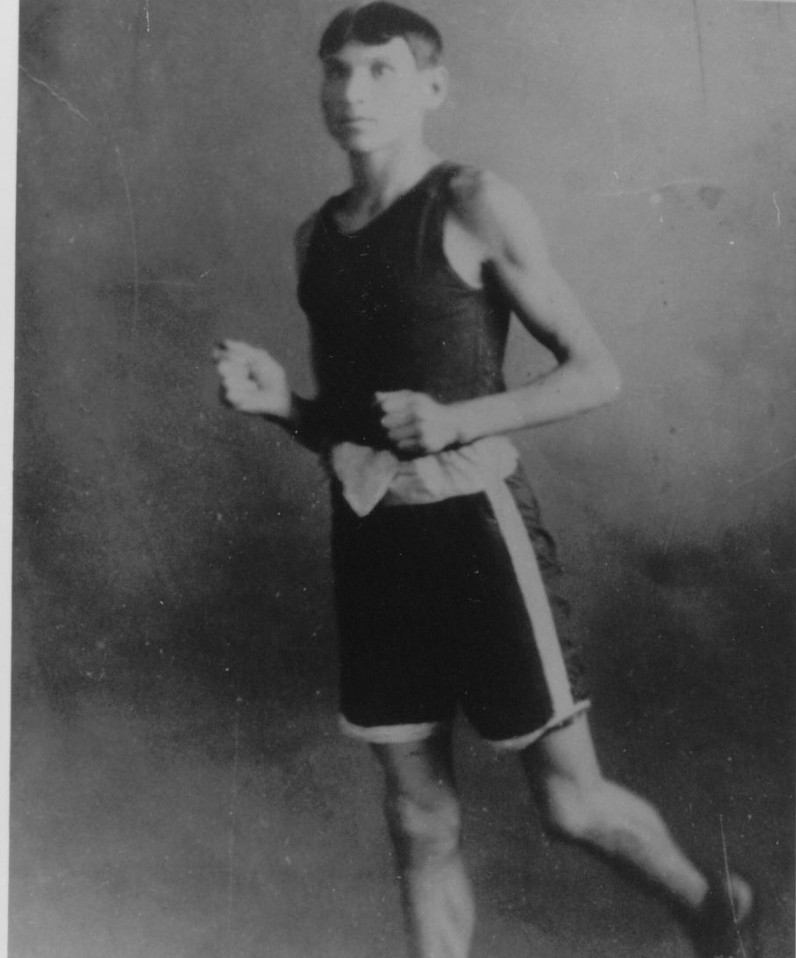

Alex Decoteau

Alex Decoteau has the distinction of being the first athlete born in what is now known as Saskatchewan to compete at the Olympic Games. Decoteau, from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation, finished sixth in the 5,000-metre run at the 1912 Stockholm Games despite suffering from leg cramps. He would also become the first Indigenous police officer in Canada and was killed serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1917 during the First World War.

David Greyeyes was another SSHF Indigenous inductee who served in the military. Greyeyes served in the Canadian Army during the Second World War. While overseas, the gifted soccer player, was a member of the Canadian team that won the Inter-Allied Games in 1946. He was chosen to represent Saskatchewan against top touring English teams in 1937, 1938 and 1949 – a testament to his longevity as a top player.

Jacqueline Lavallee and Fred Sasakamoose at the opening of the SSHF’s Indigenous sport exhibit at the University of Saskatchewan.

David Stobbe/StobbePhoto.ca

Jacqueline Lavallee was a two-sport star at the University of Saskatchewan where she was a Canadian Interuniversity Sport (CIS) All-Canadian in both soccer and basketball. She played for Canada at the World University Games twice and was a member of the women’s national basketball team for three years. She has been an assistant women’s basketball coach at the U of S for 14 seasons.

Ray Mitsuing was posthumously inducted as the first chuckwagon racer in the Hall of Fame in 2024 following his stories career that saw him qualify to compete at the Calgary Stampede for 36 consecutive years. In 1992 he won the Aggregate Championship at the Calgary Stampede and also earned the fastest time award there three times. He won the Canadian Professional Chuckwagon Association championship seven times during his distinguished career.

Jim Neilson was born in Big River, but grew up in an orphanage in Prince Albert. From those humble beginnings he would go on to play more than 1,000 games in the National Hockey League (NHL). Neilson spent 12 of his 16 years in the NHL with the New York Rangers where he played in a two NHL All-Star Games and finished fourth in voting for the Norris Trophy as the NHL’s best defenceman in 1968. He finished his career in 1979 playing alongside Wayne Gretzky during his rookie season in Edmonton.

Claude Petit also served in the Canadian Army during the Korean War and he too would compete athletically while serving overseas. Petit was a five-time Canadian Army heavyweight boxing champion and was also the only Canadian to win the British Army Heavyweight title. Inducted as a builder, Petit coached Team Canada at international competitions, worked as an official for several years and served nine years as president of the Saskatchewan Boxing Association.

Fred Sasakamoose was born in the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, but was taken from his family when he was six and suffered abuse at the St. Michael’s Residential School. Sasakamoose managed to thrive as a hockey player, being named the Most Valuable Player in the Western Canada Junior Hockey League. He made his debut in the NHL with Chicago in 1953-54 at the age of 19. His NHL career lasted 11 games, but his story had an enduring impact. Sasakamoose became an important community leader and served as Chief for six years. He reclaimed his language, becoming fluent in Cree later in life and worked to promote and develop sport programs for youth including the Fred Sasakamoose “Chief Thunderstick” Championship. In 2018 he was made a member of the Order of Canada.

Bryan Trottier is one of the most successful hockey players to come from Saskatchewan. He has won six Stanley Cups, the most of anyone in the province. Trottier scored 524 goals and had 1,425 points in 1,279 NHL regular-season games. He was also played in eight All-Star Games. The Hockey Hall of Famer wrote on the NHL website about his youth in Val Marie.

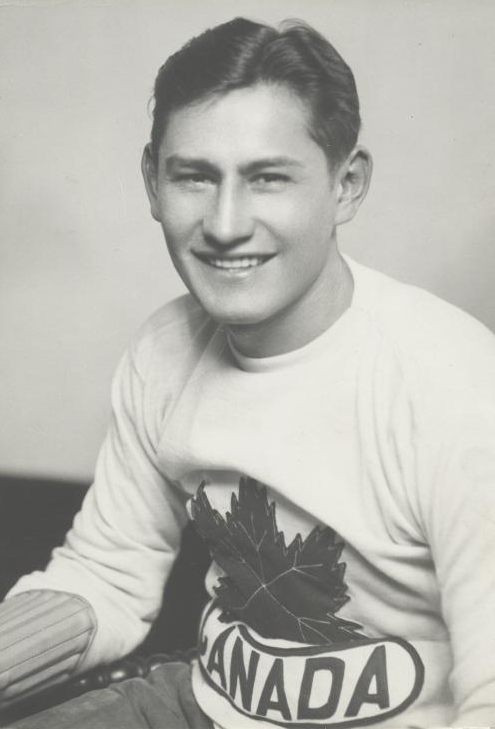

Kenneth Moore is inducted as a member of the 1930 Memorial Cup-champion Regina Pats hockey team. Moore would go on to win an Olympic gold medal in 1932 with a team based out of Winnipeg. Moore, from the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, is believed to be the first Indigenous person to win a gold medal for Canada. There is an excellent account of the toll the Residential School system had on the Moore family and how Kenneth’s parents were able to escape and spare him the same horrors that befell some of his siblings.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is proud to be located in Treaty 4 territory, home to the Cree, Dakota, Lakota, Nakoda, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame also celebrates the history of sport and the people from the land that is covered by Treaties 2, 4, 5, 6, 8 and 10. These lands have been the home of the Cree, Dakota, Dene, Lakota, Nakoda, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation.

While National Indigenous Peoples Day is an ideal time to celebrate and share these stories and resources, reconciliation is an ongoing process.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame expanded the Indigenous inductees exhibit at the Hall of Fame last year. The Hall now features an expanded permanent exhibit dedicated to Indigenous athletes and builders from Saskatchewan and this month the exhibit has a new addition — a dedicated display tablet with 5,400 words telling the stories of some of the province’s great Indigenous athletes.

In addition to the newly expanded Indigenous inductees exhibit, the Hall of Fame continues to offer Indigenous Legacies in Sport, an outreach educational program to students across the province. The Hall of Fame has also partnered with the University of Saskatchewan to create a display case and video kiosk celebrating Saskatchewan Indigenous athletes and their achievements. This exhibit is on permanent display in the Physical Activity Complex at the U of S’s College of Kinesiology in Saskatoon.