On this National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is marking the day by highlighting how two Indigenous inductees achieved their great success and achievements while enduring the effects of the residential school system.

The federal holiday was created to honour the lost children and survivors of residential schools, their families and communities. In the spirit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 87th Call to Action, the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is reflecting on some of the ways the residential school system affected our inductees. We share two of those stories here as part of our learning and reflection on our shared history.

Fred Sasakamoose was born on Christmas Day, 1933 on the Big River First Nation and would move to what is now the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation when he was very young.

Fred Sasakamoose, left, shakes hands with Chicago Blackhawks captain Alexei Zhamnov.

In his 2021 autobiography Call Me Indian: From the Trauma of Residential School to Becoming the NHL’s First Treaty Indigenous Player Saskamoose speaks candidly about his experience of being taken from his home at a young age to be placed in a residential school.

He discusses how important his family and community were in his life. His grandfather, his Moosum, Alexan, carved Fred’s first hockey stick out of a long willow branch. The young Saskamoose would skate on a frozen lake while his Moosum – who was deaf and did not speak – would ice fish and keep an eye on him.

Fred Sasakamoose wrote in Call Me Indian:

This was my world. A nēhiyaw world. A nēhiyaw life.

What I knew was that home was full of song, dance, and tradition. It was full of wonder and mystery. It was full of family, love, and community.

And then one day, in 1941, when I was just seven, all of that was taken away.

‑‑‑

To be honest, I don’t remember a lot about the beginning of that last day of my childhood. I don’t know what Frank and I were doing, only that we were outside. My father was home, chopping wood out back. I remember that, at least. And it was fall. Perhaps we were helping dig potatoes out of the ground before the first hard frosts touched them. I don’t know. The twins must have been in the cabin. Maybe three-year-old Peter was with them. It felt like a normal day, the kind you have over and over until they all blend together, stretching to the edges of memory.

Everything is a bit cloudy until the moment a huge canvas-covered grain truck appears in front of our little cabin. Three men get out of the cab. One I recognize — the reserve’s Indian agent. Another is wearing a uniform. An RCMP officer. And the third is a pale white man with a hard face. He is wearing a long black robe that billows slightly behind him as he walks. He’s talking to my mother, and my father is coming around to the front of the cabin, but I can’t make out what anyone is saying. All I can hear is the sharp, jagged sound of crying. Crying children. It’s coming from under the canvas of the truck.

And then someone is lifting the canvas flaps at the back of the vehicle. And one of the men is grabbing Frank and lifting him into the truck. My moosum is pulling me in behind his back, is standing in front of me with his arms spread. I’m peeking around him, and I see one of the men coming towards us. My grandpa tries to push him away, but he’s swept aside and falls to the ground. My strong, protective moosum, the man who is mighty enough to lift the front end of a workhorse clear off the ground, is shoved aside as if he is nothing. And then I’m being hoisted into the crush of crying, trembling children. I can see my moosum struggling to get up. He is making desperate sounds, sounds I have never heard before. My mother is hanging on to my father, her shoulders heaving. My big, strong father looks helpless.

The last thing I see before the engine starts and the flaps are dropped in front of me is my moosum, lying on the ground, shaking and crying.

And then we are gone.

Fred Sasakamoose and his brother Frank were among a group of 30 other children who were taken to the St. Michael’s Indian Residential School in Duck Lake more than 100 kilometres away. The abuse and indoctrination were immediate upon arriving.

Saskamoose wrote:

And then we were being hustled into the building. Frank and I were separated. We were marched into a room where nuns set about cutting off our beautiful braids with huge pairs of scissors and shaving off the rest of our hair with clippers. Then we were forced to take our clothes off and shuffle into a windowless brick-walled room. There, coal oil, the stuff we used in our lamps at home, was poured over our bare heads. The foul-smelling liquid dripped into my ears, stung my eyes, burned down my back.

Hot steam began to billow out from a pipe near the ceiling of the small room. Water, soap, scrub brushes. After all those hours in the filthy truck, I guess some of the kids needed a good bath. But this wasn’t a bath. It felt like those nuns and priests were trying to scrub the colour right off our skin. As if they didn’t care that my mother made sure we were washed every day, our hair clean and brushed, carefully braided, neatly tied at the ends.

Sasakamoose’s further descriptions of life at the residential school are a difficult, but important read.

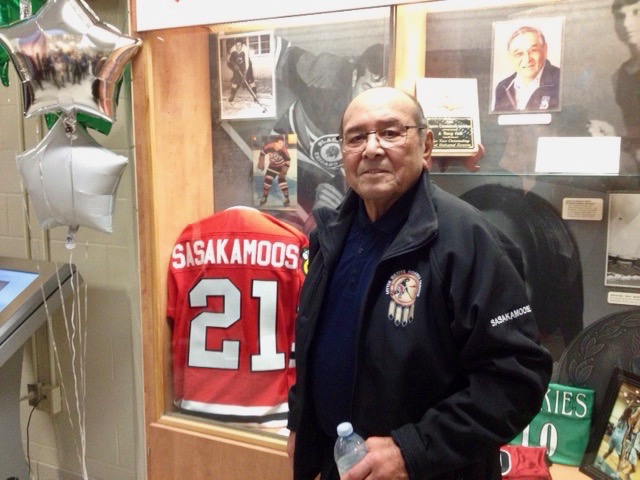

Despite all that he suffered as a child, Sasakamoose excelled as a hockey player and reached the National Hockey League as a 19-year-old in 1953 with the Chicago Black Hawks. In doing so, Sasakamoose became the first Indigenous person with Treaty status to play in the NHL.

Fred Sasakamoose with the Chicago Black Hawks Photo Courtesy : Hockey Hall Of Fame

Sasakamoose would spend 35 years as a Band Councillor of the Ahtahkakoop Cree Nation, six as Chief. He worked to give back to his community and build and develop minor hockey and other sports there.

Saskamoose’s book is available here and his story is both important and inspiring. It is worth reading in its entirety, as are the numerous other stories and testimony that chronicles the experience at residential schools.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame currently has 10 individual athletes who identify as Indigenous and have been inducted. Those athletes and builders are: Paul Acoose, Colette Bourgonje, Tony Cote, Alex Decoteau, David Greyeyes, Jacqueline Lavallee, Jim Neilson, Claude Petit, Fred Sasakamoose, and Bryan Trottier.

In addition to the individual Indigenous inductees, the SSHF also has inductees who were members of an inducted team.

Kenneth Moore, from the Peepeekisis Cree Nation, was inducted into the SSHF as a member of the 1930 Regina Pats hockey team that won the Memorial Cup. Moore is also the first Indigenous athlete to win an Olympic gold medal.

Moore was the third of eight kids born in 1910. His two older brothers had been taken to the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba – more than 300 kilometres away. The two older Moore brothers died at the Brandon Indian Residential School with no details or cause provided to the family. Kenneth would have been forced to attend the school when he turned seven. Instead, the Moore family fled the Peepeekisis Cree Nation in the middle of the night.

The family settled in Regina, which was still more than 100 km from their home reserve, but the younger Moore children were able to avoid the residential school system.

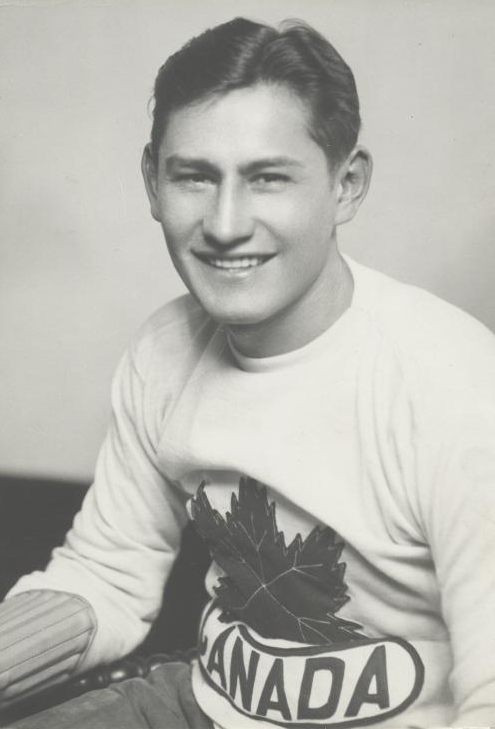

Ken Moore

Ken Moore would star as a right winger on the Regina Pats junior hockey team. In 1930, the Pats met the West Toronto Nationals in the Memorial Cup final. Moore would score the game-winning goal with 40 seconds left which gave the Pats the series win and their third Memorial Cup in six years. He also attended Campion College and Regina College on a scholarship where he captained the hockey and rugby teams.

Moore later joined the Winnipeg Hockey Club and help them claim the 1931 Allan Cup, the national amateur hockey championship. As Allan Cup champions, Winnipeg also earned the right to represent Canada at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid, New York. Canada won five games and tied one to earn their fourth straight Olympic gold medal in hockey.

These stories from our inductees are just a small example of the countless ways the residential school system impacted the indigenous population.

The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame is proud to be physically located in Treaty 4 territory, which is home to the Cree, Dakota, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame also celebrates the history of sport and the people from the land that is covered by Treaties 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10. These lands have been the home of the Cree, Dakota, Dene, Lakota, Nakota, and Saulteaux people since time immemorial and are the traditional homelands of the Métis Nation.

Today the Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame pauses to reflect on the enduring history of the residential school system in Canada, but we are dedicated to listening to and learning from the First Nations every day as we commit to moving towards reconciliation.

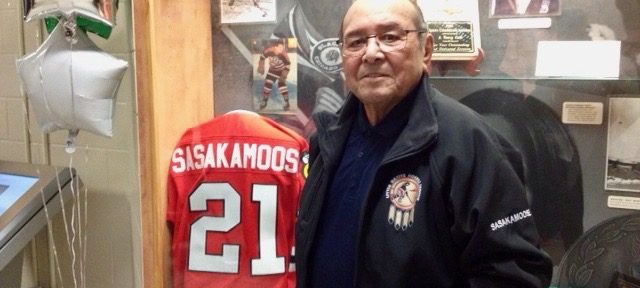

Fred Sasakamoose at the opening of the SSHF’s Indigenous sport exhibit at the University of Saskatchewan. David Stobbe/StobbePhoto.ca

To that end, the SSHF wants to continue to preserve and share the history of Saskatchewan’s Indigenous athletes. The Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame has a display case and video kiosk celebrating Saskatchewan Indigenous athletes and their achievements on permanent display in the Physical Activity Complex at the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Kinesiology in Saskatoon.

Our nomination process is open to the public and if you believe you know of an athlete, builder or team that deserves inclusion in the Hall of Fame we invite you to nominate them. You can learn more about that process here.