Lynn Kanuka remembers sprinting up and down a hill made out of garbage in Regina in the dead of winter until she was exhausted.

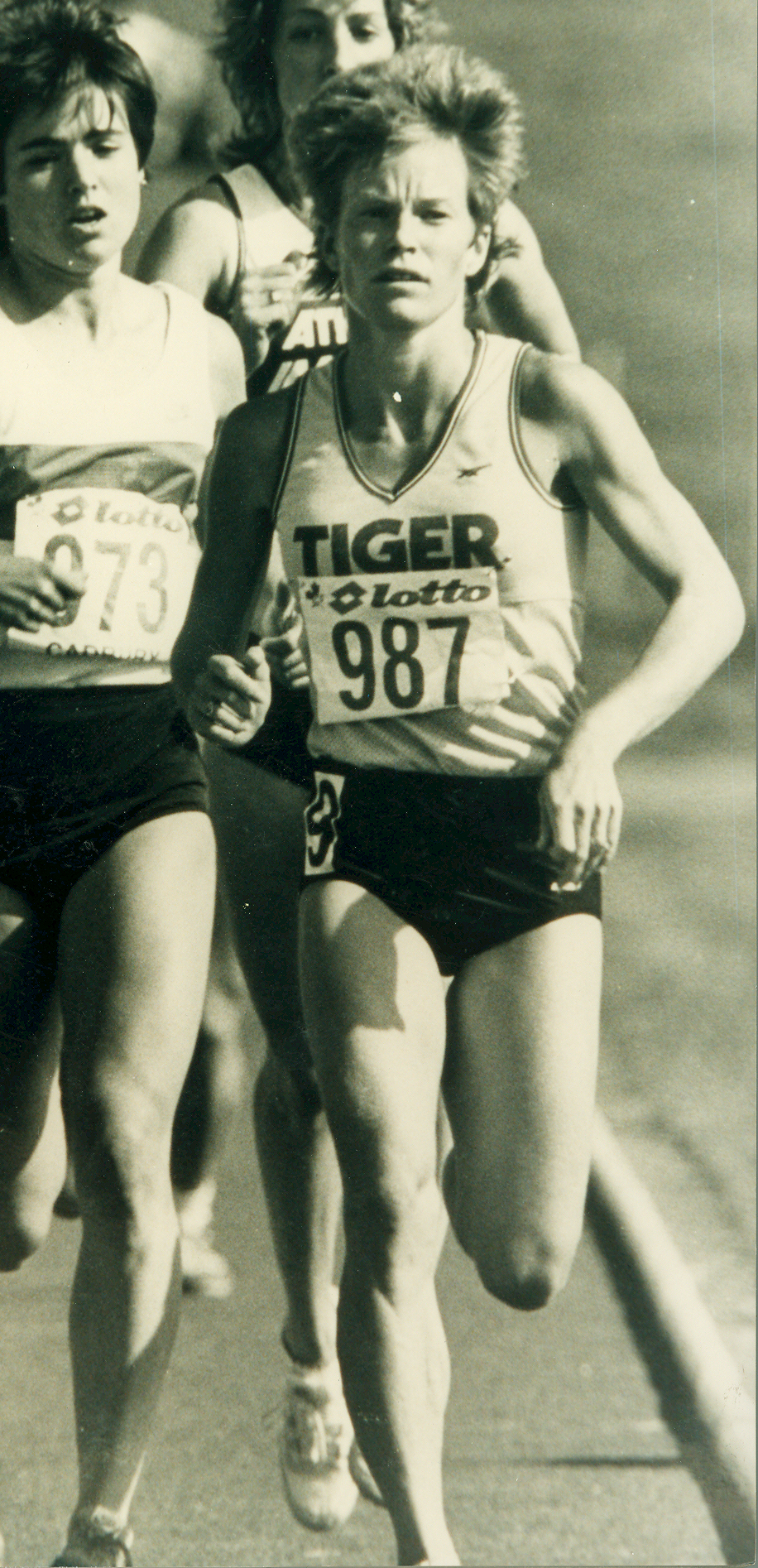

Unorthodox as it may have been, it typifies Kanuka’s grit and inner strength that helped her find a late surge that propelled her onto the medal podium. Competing under her married name of Lynn Williams, she won an Olympic bronze medal in the women’s 3,000-metre run in 1984 and a gold medal at the 1986 Commonwealth Games.

“I’m tough and tenacious. I’ve been described as the petite, little tenacious girl,” Kanuka said with a laugh.

“I was small and stocky and no one would have looked at me and said ‘you’re going to be an Olympic runner.’ Nobody would have said that. No way. But my engine is strong, I think – my aerobic engine and my work ethic. Certainly, there’s a talent factor that got fine-tuned over the years, but I was fortunate to have really wonderful people as supporters – first of all my family and then these great coaches that helped me along.”

An active multi-sport athlete who had been a competitive swimmer, Kanuka decided to start running on her own down Wascana Parkway near the University of Regina (U of R) when she was 16.

“I wanted to do something for myself. It wasn’t about sport, it was about fitness. For whatever reason, I decided I would bundle up and run out to the university and back. It was wintertime. It was cold. I didn’t have running technical clothes or anything. My friends thought I was nuts. People weren’t really doing that – and certainly not 16-year-old teenagers,” Kanuka said.

She said she had great “fun-loving prairie parents” who were supportive and threw her into sports to keep her out of trouble. Her father had been an athlete, but still, she was surprised when he saw her going out for a run and offered to go with her.

“That was pivotal,” she said. “He could have said ‘why are you going to do that, it’s -30C outside’ or ‘you should be helping your mother make dinner in the kitchen.’ He could have said that, but instead he said ‘well wait a minute and I’ll come with you.’

“He huffed and puffed and we got all the way out there and I was about to turn around and go back. There’s that garbage dump hill out there, covered in snow and he said ‘we’re all the way out here, why don’t you run up and down that hill a few times.’ I never argued with him and now I was huffing and puffing. I loved it. I loved working hard. It felt good to move and breathe and have my heart-rate go up. And that was probably my first running interval session.”

She had run track, but in her senior year at Regina LeBoldus, she decided to run cross country instead of playing volleyball and won the high school provincial title. After high school, she trained in Regina under the guidance of coach Larry Longmore at the Wheat City Kinsmen Track Club. She competed at the 1977 Canada Games in St. John’s, NL and also attended the Legion Track Championships as she got her first taste of national-level competition.

“Those things are very pivotal and they nudge, nudge, nudge you along with more experience,” Kanuka said. “Along the way you have these people – if you’re lucky like I was – who also nudge you along and that little voice in your head tells you you’re on the right path.”

After two years at the U of R – which did not have a track program at the time – Longmore encouraged her to transfer to the University of Saskatchewan to work with Huskies track coach Lyle Sanderson (himself a Saskatchewan Sports Hall of Fame inductee in 1994).

“Lyle was a great coach and mentor and father of fun I would say,” Kanuka said. “He was coaching Diane Jones Konihowski and they had quite the program there over all of those years and so that seemed like a good idea to me. That was a pivotal year. It was only one year, but it felt so much longer.

“Things are so different now. We had a gym, a regular gym, and we would have a full track team practice going on in there. Lyle arranged for the construction of wooden corners… It was small, small quarters, but everything was so well organized and orchestrated. Now, of course, there’s a field house. There are good things about having facilities, but there were many good things that happened when we were tough and close and resilient in those days and in those conditions.”

While she had been focused on attending medical school in Saskatoon, Kanuka made the national cross country team and won a university championship and Sanderson suggested she could get a college scholarship in the United States.

“I still wasn’t committed really. I didn’t understand what I could maybe achieve at that stage. I was just going along with it. At that point, I didn’t really have an Olympic dream,” Kanuka said.

She went to the library and sent letters to all of the warm-weather universities that “seemed like they would be cool places to go to” and settled on a scholarship to San Diego State. There she competed in a number of distances from the 800m to the 10,000m and was often injured.

“I had a wonderful experience down there, but there were challenges. I ran injured a lot. Every summer I never had a Canadian track season because I had to run so much,” Kanuka said.

Kanuka made her IAAF World Cross Country Championship debut in 1979 and competed there for four straight years. However, she didn’t make her outdoor debut internationally until 1983. At the ’83 IAAF World Championships, she finished 10th in the 3,000m but ran the same time – eight minutes, 50.20 seconds – as the ninth-place finisher. American Mary Decker won the race and West German Brigitte Kraus was second ahead of a pair of runners from the Soviet Union, including three-time gold medalist Tatyana Kazankina.

Having married fellow 1984 Olympian Paul Williams in 1983, she had almost considered her running career over.

“I was finished, I thought,” she said. “I was injured again and I thought I would go apply for med school. He said ‘Lynn, you never really got to be who you could be as a runner because of all of the racing and the injuries.’ He said ‘give it one more year and focus on the Olympic trials and see if you can make the Olympic team.’ That’s when a light went on for me. I thought I’ve been doing this for so long now, why don’t I focus on this and see what happens?”

Kanuka qualified for the Olympic team and she would compete in the first women’s 3,000m in the Olympics. It would be one of the marquee events of the Games.

After winning two gold medals at the IAAF worlds, Decker had been named Sports Illustrated’s Sportswoman of the Year – only the second time in 30 years that a woman had won the honour alone. Decker made her international debut at 15 – sporting braces and pigtails and weighing 89 pounds – and endeared herself to the American public by throwing a baton at a Soviet runner who cut her off during an indoor race in Moscow. She had broken seven world records by the time she made her Olympic debut in 1984.

While the Eastern Bloc boycott meant that the top Soviet runners would not be present, there was some controversy about one runner who would be at the Games. Zola Budd was an 18-year-old South African runner who competed barefoot. With sanctions placed on South Africa due to their government’s apartheid policy, Budd had rarely competed internationally. However, she opened some eyes when she unofficially broke the world record in the 3,000m at a race in South Africa. That spurred an English tabloid to note that she had a British grandparent and champion her cause. Budd received her British citizenship in short order and not without some controversy.

Budd wasn’t the only runner posting great times. At Swangard Stadium in Burnaby, B.C., the Canadian team was preparing for the Games and Kanuka ran the fastest time in the world in a time trial. The world record can only fall in an official competition, but still, the time she posted was valuable three weeks before the Games.

“We were so excited. We celebrated. ‘Oh my God, you’re so ready!’ I knew that I could run with anybody that was going to be there. So I was very excited. Nobody was looking at me and I knew I could be in that final,” Kanuka said.

Before the Games, the Canadian middle-distance runners trained together in Lynn’s old stomping grounds of San Diego. She qualified in second place in her heat, behind Decker who won in Olympic record time.

“Dieticians don’t like it when I tell this story, but the night before I went out for dinner with one of my coach/mentors – Dr. Jack Taunton, he was a pioneer in the world of sport medicine – and for my last supper before the Olympic final we had pizza and a beer together,” Kanuka said. “Good prairie girl… we used to always have a Friday night beer and pizza night, so that was really familiar. It was a beautiful evening and I said ‘well Dr. Jack, I’m ready. There’s no reason not to go out there and run my heart out.’”

Thelma Wright, herself a former Olympic runner, was coaching Kanuka in Vancouver. Wright would give birth to a future Olympian during the Games back in Canada.

“She was great for me and in fact, I broke her (Canadian) records in the 800 and 3k, so that was really cool,” Kanuka said. “The day before the final she sent me a telegram: ‘Lynn, your godson Anthony Madison Wright came out fighting today and that’s what you need to do tomorrow.’”

With some inspiring words from her coach, a blazing training time fresh in her mind, and at ease in Southern California, the stars aligned well for her Olympic debut.

“I was nervous. There was so much hype, but I was ready. It helps when you’re ready. At least I had gone to the worlds in ’83, so that helped,” Kanuka said. “For me, I was a relatively unknown Canadian. Certainly, no one was focusing on me to win a medal.”

As it happened, the women’s 3,000m would not only live up to any pre-race hype, but it would go down as one of the most memorable races in Olympic history. Kanuka’s fighting spirit would hold her in good stead.

“On the day, what a crazy race that was, just crazy,” Kanuka said. “My plan was to tuck in the middle. It was going to be predictable that Mary Decker and Zola Budd were going to vie for the lead. They’re both front-runners. They like to lead. That’s how they are. But there’s danger in that. The track is narrow and only one person can be in front. I thought they would set the pace and I would tuck in there.

“I have what we call ‘good turnover.’ I’m small, but I can get my legs going quicker, so I get the jump on people and I can pass quicker and hopefully, they can’t react. That was always a strategy of mine.

“It was so bumpy and jostly and it was very fast. It was a world record pace the first few laps. We were working really hard and I was getting bumped around. You can’t really see it on TV, but it was not easy going.”

Kanuka settled in on the inside lane and sat in fifth or sixth throughout the opening laps. After four laps, Budd inched into a lead and with Decker on her heels, the pair collided and Decker fell into the infield having injured her right leg. Decker would contend that the inexperienced Budd had cut inside too quickly after her pass. Budd would be initially disqualified after the race for obstruction, only to have her result reinstated an hour later after a review of the tape. The incident would be debated for years, but at that moment the 93,000 people in the Los Angeles Coliseum voiced their shock and displeasure at seeing Decker hit the ground.

“I saw they bumped and then boom, Mary goes down. We all had to do a dipsy-doodle and avoid the collision, Kanuka said.

A lap earlier American Joan Hansen had collided with New Zealand’s Dianne Rodger and fell, but got up to finish the race. Behind Kanuka, Brigitte Kraus – the world championship silver medalist – had also hit the ground.

“When we came around there’s Brigitte down and I assumed – I think as we all did – that Mary went down, but she would get up and rejoin the pack somehow. Then there she is, still down as we do another lap and then you’re thinking ‘my God, Mary Decker is out’ and I remember the crowd – it started with this great roar – and now they’re booing like there was foul play,” Kanuka said.

Decker and Kraus would not finish the race.

Budd, Britain’s Wendy Sly and Romanian Maricica Puică were bunched with Decker when she fell and had broken away from the rest of the field.

“We all lost focus. It went from being in a pack to everyone being spread out around the track,” Kanuka said. “There were literally a couple of laps where I remember nothing. I just remember running in this weird vacuum and hearing all of this booing. Then I woke up. I heard the bell and it was ‘holy crap, it’s the last lap, wake up!’

“I looked and I’m in fourth and I could see that Zola Budd was coming back. The bear had jumped on her back. If anybody lost focus, she probably did. She had no gas. I thought ‘if I can go by her I’ll be in medal contention.’”

As Budd faded, Kanuka surged, catching her on the final backstretch.

“I passed her and now I was really running. I was racing for my life, but I knew that everybody else was waking up too. I could hear them,” Kanuka said.

Puică had more in the tank than Sly and won comfortably with Kanuka claiming the bronze medal in a time of 8:42.14.

“It was an amazing day,” Kanuka said.

“It was a great race, but it was not my best race. It was just the one that got the most attention. I was a much better, stronger, seasoned, experienced athlete in the years following.”

Two years later, on a cold, windy day in Scotland, Sly would enter the Commonwealth Games as the favourite alongside Scottish runner Yvonne Murray. Two years on, Kanuka was definitely not flying under the radar anymore.

“That was probably one of my favourite strategic races because it was super cold and windy,” Kanuka said. “Yvonne and Wendy are taller than I am and Yvonne likes to lead, so being small I was going to tuck in, but no one wanted to lead that race because it was so windy.

“For four laps it was painfully slow. I knew I had the gears and I would have to go at some point, but I was hoping someone else would go and I could match it and then I would go with 500 metres left and see if anyone could stay with me and keep something in reserve and bust out in the final turn. That was my plan and it really worked.”

When Murray broke from the pack, Kanuka took her time reeling her in and then stuck with her. Kanuka tried to kick with 500 metres left, but Murray matched her late surge and passed Kanuka with 300 metres remaining.

“I remember thinking ‘come on Lynn, you can catch her.’ With 150 to go off the turn, I bust out and passed her and she couldn’t match it and that was it,” Kanuka said. “That was a great one. That was one of my favourite races.”

Kanuka returned to the Olympics in Seoul, South Korea in 1988. She opened the Games with a disappointing eighth-place run in the 3,000m but finished her Olympic career with a strong fifth-place finish in the 1,500m.

Between those two races, Canadian sprinter Ben Johnson failed a drug test, was stripped of his gold medal in the 100m and created a major distraction within the Canadian delegation and the track team.

“I personally had one of my best races in the 1,500, but of course the Ben Johnson scandal happened and that was awful afterward,” Kanuka said. “I ran my best time. I finished fifth, but it was a crazy race too.”

Kanuka had grown to prefer the 1,500m and finished in a time of four minutes and 86/100ths of a second. She was 62/100ths of a second out of second place in a frenzied finish.

“That’s how close it was,” Kanuka said. “That was a really great race. That was one of my best races ever, for sure.”

Romanian Paula Ivan won the 1,500m in an Olympic record time of 3:53.96 that still stands in a dominating performance. Two Soviet runners rounded out the medals.

Four women’s running world records and four more Olympic records still stand from the 1980s. Those times have done little to quell the suspicions of drug use that surrounded the era even before Johnson’s positive test.

“There were others in our midst as well who were dabbling in that world of performance enhancements. There were rumours flying around and scandalous things that were happening,” Kanuka said. “I didn’t really focus on that.

“I just tried to beat them. That’s the name of the game, get to the line first. Was it frustrating – if I really get going on it? Yeah, for sure, but I’m a cup-half-full kind of gal. Why focus on that? It’s just negative.”

Kanuka makes her home in White Rock, B.C. where she has four children and coaches Canadian Olympian Natasha Wodak, the Canadian record-holder in the 10,000m, amongst others. While she does coach elite athletes, Kanuka believes “movement is medicine” and is just as passionate about inspiring people to be more active.

“That’s really become my passion. I love helping people take steps to better health and enjoy the sport I love,” she said.

“I’ve worked a long time now – a dozen years or more – with our Indigenous population out here in B.C. When I first started we had three leaders that I trained to coach and lead the running and walking programs. Now from three leaders in one tiny training session, we now have five regional leader training events and we train at least 100 leaders every year and over 2,000-plus people who are mobilized in running and walking programs. This is not about performance, it’s about personal well-being and the kind of wheel of health that we know exists, we just have to tap into it.”