As the sun began to set below a cloudy autumn prairie sky, quarterback and captain Albert Townshend shouted signals to his fellow Moose Jaw Tigers. The Tigers centre rolled the football backwards with his foot to start the play. Townshend crouched, picked the ball up and spun the ball underhand wide towards the sideline. Reading the play, Regina’s Ted Porter intercepted the lateral before it could reach Tigers halfback Dewart Bissell. Porter quickly dodged the remaining Moose Jaw backs before they had fully recovered from the surprise and quickly broke away into the clear. After running 80 yards, Porter touched the ball down into the grass between the uprights at the Moose Jaw Baseball Grounds.

Porter had just scored the first touchdown in Saskatchewan Roughrider history.

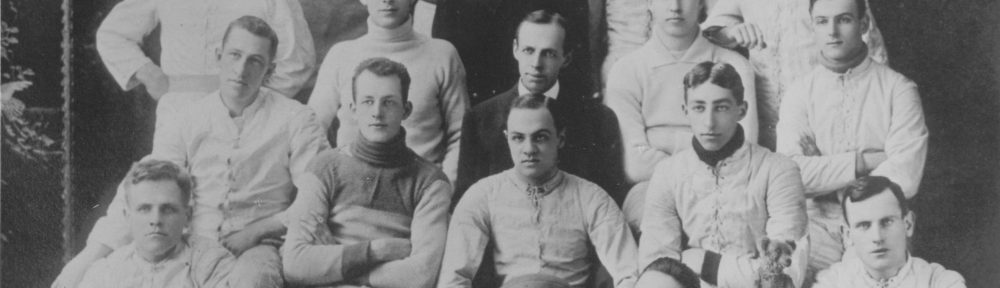

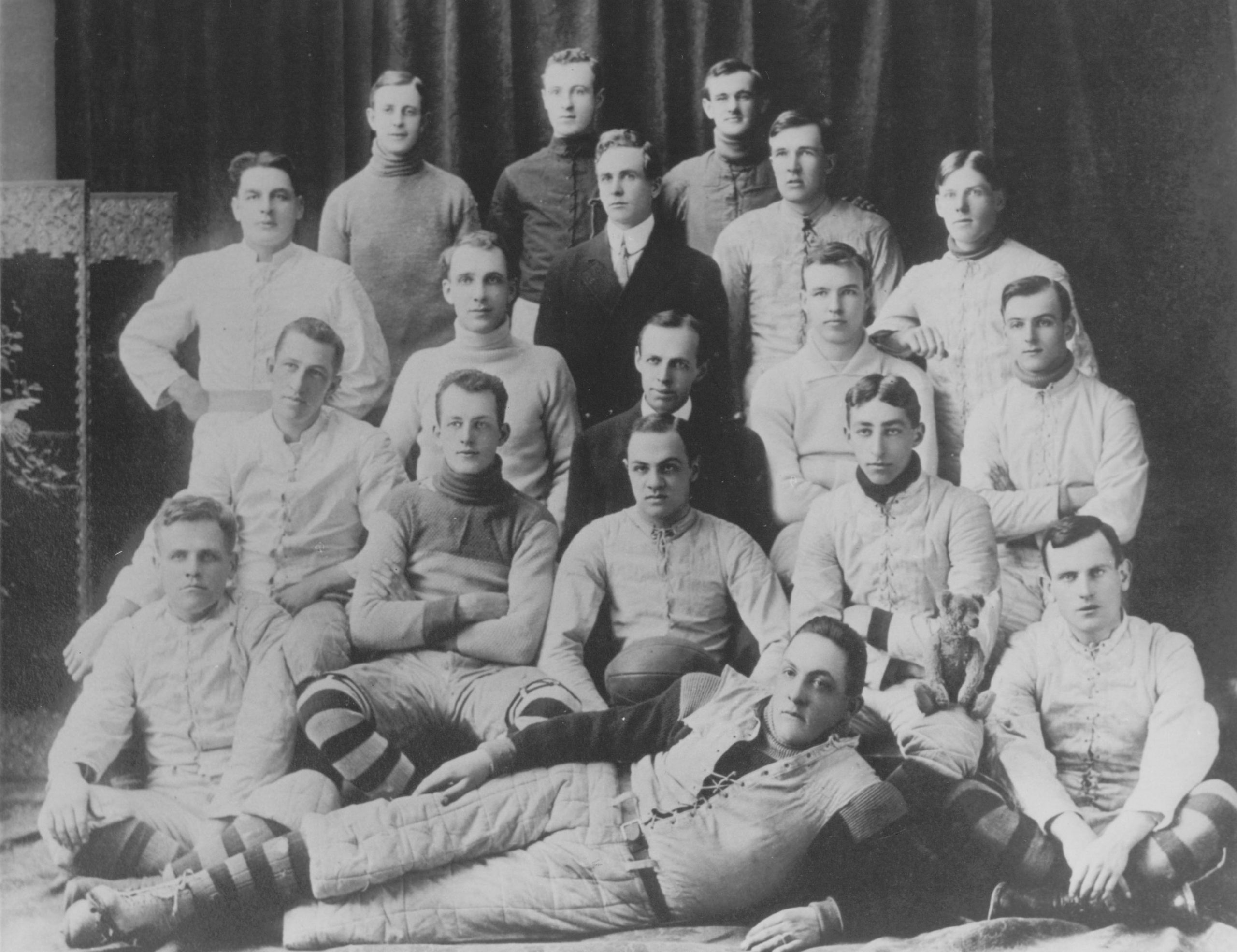

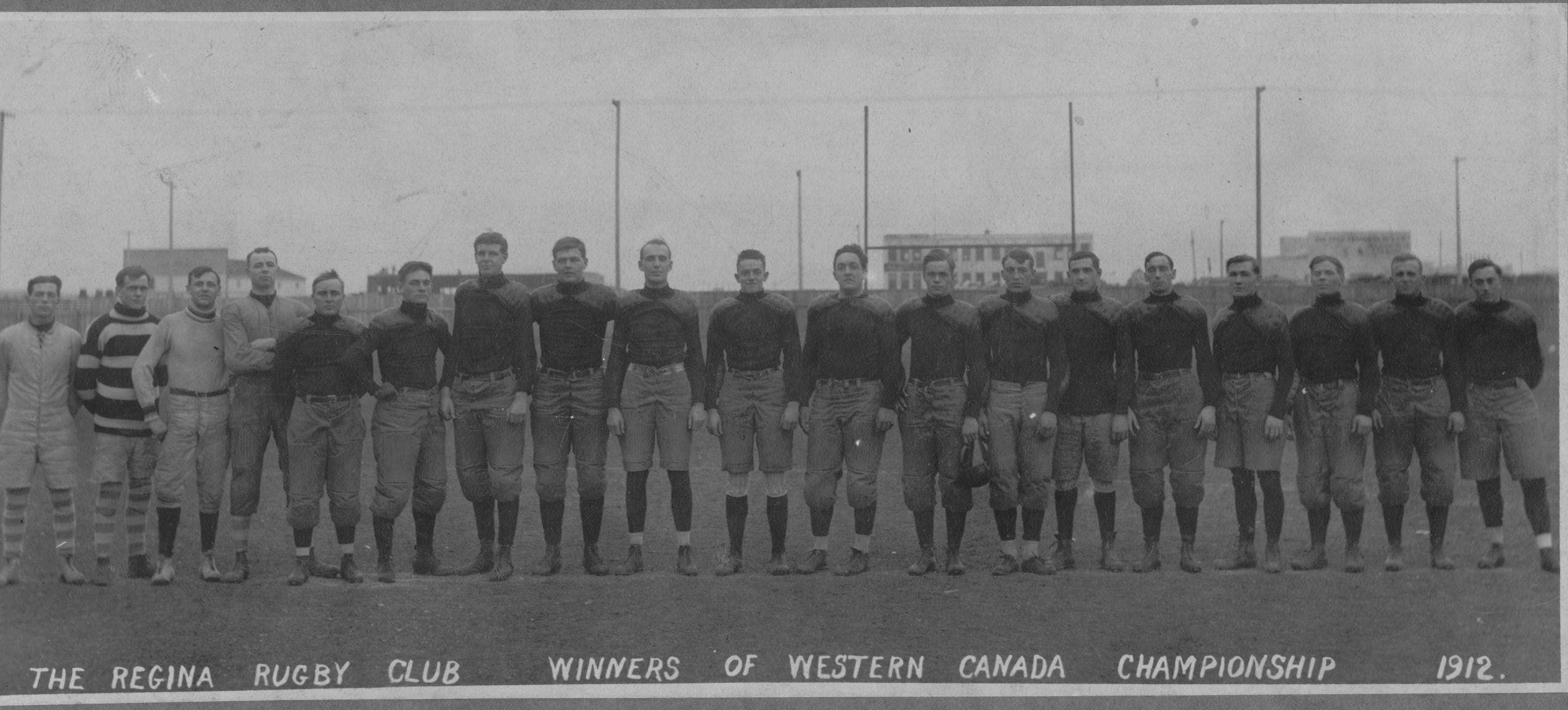

Regina Rugby Club, 1910: “Billy” Ecclestone (back left), Jas. D. Scott, Pete Green; George Lythgoe (second back row left), M.J. O’Brien, John V. Lackey, R.L. “Dinny” Hanbidge; “Roy” W. Hamilton (third row sitting left), Alex. Page, W.J. Bright, Chas. Galvin, H. Hoppins; Harry B. Froste (front row, left), L.C. Duncalfe, E. “Ted” Porter, “Tommy” Blair, Allan R. Ferguson; Courtland “Slabs” Merrick (front row, reclining). Missing: “Al” Urquhart.

One hundred and ten years ago today the Regina Rugby Club played their first game of rugby football in Moose Jaw. In the century that has passed, that rugby club has changed names, colours and leagues, but with each autumn the tradition that is the Saskatchewan Roughriders grows.

The birth of Riders football took place in Moose Jaw on Oct. 1, 1910.

This is the story of that game, the first football season in the province and the origins of the game.

* * * *

Rugby football was a new sport in the west at the turn of the 20th century. Beginning to gain in popularity in the east, the Canadian Rugby Football Union was formed in 1882 after the game was played on eastern campuses as far back as 1861.

Members of the North West Mounted Police stationed in Regina brought the game west with them. The Mounties took up the sport as early as 1886 and soon formed a team that challenged their Winnipeg counterparts. The game was played informally, but as more young men heeded the call to go west, the desire to organize grew.

The Regina Rugby Football Club was formed at a meeting at City Hall on Sept. 6, 1910. A day later, the Regina team began to practise at Railway Park every day at 5:30 p.m., giving the players at least an hour of daylight after work to learn the finer points of the game.

In addition to their outdoor practices, the Regina team also held “chalk talk” practices once a week at night when they discussed strategy and signal calling. Crucially they also discussed the rules which still often varied by region and league.

Both teams would field 14 men who would play both ways. There were five substitutes ready in case of injury, but once a man was substituted, he could not return.

At a meeting at the Flanagan Hotel (now the Hotel Senator) in Saskatoon on Sept. 22, the Saskatchewan Rugby Football Union was founded by representatives from Regina, Moose Jaw, Saskatoon, Weyburn and Prince Albert. Given the speed with which organized rugby football was moving, only Regina and Moose Jaw fielded teams for a shortened 1910 season.

The teams would meet four times to decide the provincial champion.

* * * *

Septimus (Seppi) DuMoulin was instrumental in the creation of the Moose Jaw Tigers. DuMoulin, a banker, had relocated to Moose Jaw. The former player and official in Ontario Rugby Football Union brought his know-how to the Friendly City and named the team after his former club — the Hamilton Tigers. In 1950 the Tigers and the Hamilton Flying Wildcats would merge to become the Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

After coaching Moose Jaw’s Tigers, DuMoulin would conclude his 1910 football season on Nov. 26 when he returned to Hamilton to coach the Steel City’s Tigers in the Grey Cup. The Hamilton Amateur Athletic Association Grounds was filled by 12,000 fans in the stands and hundreds more who knocked down the outside fence and perched on the scoreboard for a view of the action. They saw the Tigers lose the second Grey Cup 16-7 to the University of Toronto Varsity Blues.

DuMoulin would be the only man to go on to hold chief offices in all three major football unions — including a term as president of the Interprovincial Rugby Football Union in 1932. He was inducted as a charter member of the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

* * * *

Though the game was new to many, anticipation was high before the first game. Both city’s newspapers invited players to open tryouts. As the teams took shape, fans gathered after work to watch the open practices and speculate on their chances.

The Regina team already enjoyed the support of the “15th Man” before it had even kicked off their first game. For the Saturday afternoon opening game, 150 fans paid $1.25 each for return fare on a special train to Moose Jaw. There at the Baseball Ground, they were joined by 600 local fans under cloudy skies but with the weather a comfortable 15C.

The crowd was enthusiastic, though a touch confused by the nuances of the rough spectacle laid out before them.

The Moose Jaw Morning Times reported that “a good many of the spectators, being unfamiliar with the game, hardly knew when to yell, but they thought they were right in going to it when a Regina man was bumped.”

The Regina fans may have been out-numbered, but they weren’t shy about letting their neighbours know that they were there. According to Moose Jaw’s Evening Times, the Regina fans “never failed to make themselves heard and encouraged their favorites right heartily.”

* * * *

It turns out that “games are won in the trenches” may be a cliché as old as the game itself.

After the dust settled on the first rugby football game in the province’s history, the writers of the day were unanimous: size matters.

Moose Jaw Evening Times summed up the first game succinctly in their subhead: “Home team superior in weight and playing ability.”

The story explained that “the Moose Jaw boys could control the scrimmage very much as they liked, while the backs were showing well in judicious rushes.”

The Moose Jaw line trio of Grayson, McDonald and Cochrane each weighed 175 pounds. Incredibly that provided a huge 20-pound average weight advantage in the trenches. Moose Jaw used their size to pound the ball directly at the Regina defence. One of those undersized Regina scrimmage men was Robert Leith “Dinny” Hanbidge who would become a member of Parliament and the party whip in the Diefenbaker government and would go on to be the province’s 12th Lieutenant-Governor, serving from 1963-70.

Depending on which account of the game you trust, either side had the better of a scoreless opening quarter.

The Evening Times felt that “From the kick-off the ball was kept in Regina’s territory and the Moose Jaw scrimmage took control of the ground by bucking the Capital city boys off their feet. Robbins, Townshend and Johnson were noticeable and time and again went through the opposition to the requisite distance as easy as wind through a sieve. But Regina fought better with their feet on their own goal line and managed to keep out the Tigers in the first quarter.”

Regina Morning Leader felt that the Queen City boys — resplendent in the regal colours of purple and gold — “were in the game all the time and had the play in Moose Jaw territory a good part of the game.”

In either case what happened next is a matter of fact, not opinion.

The Tigers finally found their breakthrough when Townshend, their quarterback and captain, was able to bull his way 10 yards through the stubborn Regina resistance to score the game’s first touchdown.

When Robbins failed to kick the convert, Moose Jaw held a 5-0 lead.

The Tigers built on the lead when a Bissell punt forced Regina’s halfback, Miller, into his end zone where the ever-present Townshend tackled him for a rouge to go ahead 6-0.

Regina failed to make much forward headway and Townshend capped a drive late in the second quarter with his second touchdown. Another failed convert gave Moose Jaw an 11-0 half time lead.

The lead either gave the Tigers a false sense of security or lit a fire under the Regina boys — or both. Either way the visitors came out for the second half and began to move the ball — and more importantly — win the battle along the line of scrimmage.

The Evening Times noted that Regina “more than held their own for the only time in the game and the team was able to make ground: but the homesters always tightened at the right moment and nothing came from their efforts . . .”

Regina captain Charles M. Galvin’s punt was fumbled by Tigers fullback Scythes which led to Moose Jaw conceding a single to cut the lead to 11-1.

The Tigers responded in the fourth quarter by pinning Regina deep into their own end repeatedly and not allowing them past their own 25 yard line.

It was there with the Tigers driving to try to extend their lead that Porter read Townshend’s intentions and breakaway for what the Morning Leader called “the outstanding feature of the game.”

Porter was certainly less green than many of the other players on the field. The Regina wing had formerly played for the Toronto Argonauts, as did Regina’s first quarterback Allan Ferguson. The Toronto club was formed in 1873 when the Toronto Argonaut Rowing Club decided to form a rugby team.

Regina also had a winger named Sheriff who had come from the Queen’s University side in Kingston. Jim Scott had played for the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association team — Montreal AAA is the oldest sporting club in the country. Their hockey club won the first Stanley Cup in 1893 and would win three more. In 1931 they won the Grey Cup.

Townshend was a constable with the Moose Jaw Police. The “big, husky, ex-Hamilton Tiger” — as the Regina press called him — used his experience to keep the Tigers in possession and on the attack. Moose Jaw also had other seasoned players like Bissell, Robbins, Johnson and Duff who were prominent because of their experience.

Despite their limited time to prepare and many of the players’ limited experience, both teams demonstrated good ball handling and didn’t fumble the ball often.

After Porter cut the Moose Jaw lead to 11-6, the woeful performance of the kickers continued as Galvin missed the convert despite being located right between the uprights.

Once again the Tigers forced Miller to concede a rouge before the Tigers added a final touchdown in a bizarre fashion.

Bissell’s long punt went over the Regina backs and into the end zone. Believing the kick would count as a rouge (or a kick-in goal as it was sometimes called) and that the ball was no longer live, they let it lay there. Which is where Moose Jaw winger Law flopped on it to score the final touchdown in the 17-6 win.

The Regina newspaper account of the game makes no mention of the second Moose Jaw rouge and reported the score as 16-6.

* * * *

It is worth noting that DuMoulin, as the president and coach of the Tigers, refereed the game.

It was common in the early days of the sport to have representatives of the clubs officiate the games. Often one team would provide the referee and the other the umpire. Sometimes the men would switch positions at half.

In Regina, the Morning Leader made a point to complain about the officiating saying that DuMoulin was allowing Moose Jaw to get away with “off side interference.”

“(DuMoulin) a few years ago was one of the best rugby officials in Canada, but he seems to have neglected his foot ball education since coming to this province. At one stage of the game, Scott, of the Regina team, so strongly objected to his decisions that he was ruled off for two minutes.”

* * * *

A week later the teams met again in Regina. Moose Jaw sent 200 supporters east by train. Admission to Dominion Park was a quarter and the crowd that paid their two bits saw Moose Jaw win a very close 7-6 game thanks to another missed convert attempt by Regina.

In that game Regina was bolstered by a handful of skilled reinforcements. Most notably quarterback Billy Ecclestone — another former Hamilton Tiger — took the reigns. Like Porter, winger Clarence Dale had previously played with the Argonauts. Doc Stringer had an impressive resumé as he had played U.S. college football at the University of Wisconsin and then had played with the Calgary Caledonians in ’09.

After the close win, the Evening Times stated that club officials felt that “the game revealed one or two defects that must be remedied by Saturday.” So daily practices continued and a call went out for “all the regular players, and anyone interested or ambitious enough to try and win a place on the team . . .”

The third meeting of the season proved anticlimactic. Ecclestone could not leave his business commitments and Moose Jaw capitalized on five Regina fumbles in a 38-0 rout to clinch the provincial title at the Baseball Ground.

They completed the season sweep with a 13-6 win.

It is the only winless season in Roughrirder franchise history.

The Tigers weren’t able to challenge the Manitoba champions — the Winnipeg Rowing Club — because they were not part of a recognized amateur association. The next fall the Western Canada Rugby Football Union was formed to rectify the problem with nine teams representing the prairie provinces.

Wanting to build on their great 1910 season, the Tigers’ manager, Walter Ross, offered to pay all of the expenses for the Calgary Tigers if they would come to Moose Jaw on Nov. 12, but the game never took place.

In 1911, Regina changed their colours to blue and white — they would wear red and black in their third season — and claimed the provincial title. They were set to play Winnipeg before foul weather forced them to default in dubious circumstances. The Calgary Tigers beat Winnipeg 13-6 to claim the Hugo Ross trophy as the first Western Canadian champions.

Ross, a Winnipeg realtor, donated the championship trophy and less than a year later would die aboard the Titanic.

In 1912 the Regina Rugby Club won the Western Canada Championship after finishing their debut season winless in 1910.

The men representing the two cities weren’t the only ones making history on the gridiron in 1910. The Regina and Moose Jaw Collegiate Institutes engaged in what is believed to have been the first organized high school rugby football game played in Saskatchewan.

The school, now known as Central Collegiate, hosted Regina on Oct. 29, 1910 suffering a 23-2 defeat.

Moose Jaw Collegiate Institute was in its first semester in its new building. Their first starting 14 featured: Grayson, Sifton, McKay, Moffatt, Knight, Kern, McGillivray, Johnson, Cunningham, Cochrane, Rorison, Paul, Pascoe and Emerson.

Moose Jaw actually took an early 2-0 lead thanks to a pair of singles by their kicker Moffatt. Regina took a narrow 5-2 lead into the half, but their superior backs coupled with Moose Jaw’s poor tackling led to the game getting away from them.

Two days later, Moose Jaw traveled to Regina’s Dominion Park where they lost 23-5 to Regina before a crowd of 800 people.

The Evening Times saw a lot of promise in the teens despite the scores.

“Although beaten the local boys made a good enough showing to warrant a belief in their ability to make a good team, but they suffered obviously from a lack of experience.”

Rules constantly evolving to make game safer and more open

In 1910 rugby football had a foot in each sport that made up its name.

Many of the key early rule changes that turned rugby into football had already been established. However, with no forward pass, the game would have looked significantly more like rugby than what Canadian Football League fans have enjoyed for years.

Of the key differences between rugby and football, the most basic is one of the most crucial — the team in possession started each play by ‘heeling’ the ball back to their quarterback. While similar to a scrum in rugby, the right of possession divided teams into offensive and defensive sides on each play.

Teams had three plays to gain 10 yards for a first down. Three men were required on the line and they couldn’t move until the ball was heeled back. A yard had to be given by the defence. There were 14 men on the field — as opposed to the 15 in rugby. The Ontario Rugby Union was using 12 players as early as 1903, but the Canadian Rugby Union and other leagues in the country were slower to change.

A touchdown (or try) was worth five points. A goal from a try – a convert – was kicked from the 35-yard line and worth a point. A goal from the field was four points. A free kick was three points and a penalty kick was two points. A rouge was a single point scored off of a punt or a missed field goal when the player receiving the kick was tackled in the end zone.

Many of those changes were the so-called Burnside rules named after University of Toronto captain Thrift Burnside who took many of the innovations Walter Camp was making in the U.S. college game.

When McGill University went to Cambridge, Mass. on May 13, 1874 they met Harvard in the first rugby football game in North America. It could be said McGill brought rugby football to the U.S. as their use of their hands to pick up the ball helped take the game away from soccer. The innovation impressed the Harvard team and the two games the teams played were played first under the “Boston Rules” and the second under the “Canadian Rules.”

Those compromised rules continued to evolve separately in each country.

The forward pass had been legalized in the American college game in 1906 after American president Theodore Roosevelt demanded change after the 19 deaths the year previously. The forward pass wouldn’t be legal in the Canadian professional ranks until 1929. It was felt at the time that with the wider field, the Canadian game didn’t need to be opened up.

In 1910 teams were still using three downs on both sides of the border. The Americans wouldn’t add a fourth down until 1912.

In the U.S. 1910 was a pivotal year in the development of the game.

While violence and death had long been a part of U.S. football — and part of its early appeal. Major changes were made after the deaths in 1905, but the last straws appeared to have been broken in 1909.

Army’s captain Eugene Byrne died after suffering a dislocation between the first and second cervical vertebrae while tackling Harvard’s Wayland Minot.

Army cancelled the rest of their season, but two weeks later Virginia freshman halfback Archer Christian died in a game in Washington, D.C. The death in the capital so soon after Byrne’s death led to renewed cries to have the sport abolished.

Instead major changes were made. The need for seven men on the line and the abolishment of motion at the snap of the ball came into existence. Previously, only the centre was on the line as he snapped the ball, allowing the lines for both teams to be already moving at each other at the snap of the ball. The committee also tried to curb dangerous pile-ups by ruling that a player was down once their knee or elbow touched the ground.

The forward pass was upheld and some of its restrictions were rescinded. When added in 1906, a pass had to be touched by a player on either side before it hit the ground or else it resulted in a turnover. Under the rule change in 1910, it merely resulted in a loss of a down.

Those changes helped make football a far more vertical game and uncrowded the line of scrimmage. The game had taken a huge leap forward in its evolution.

This story was first published in the Moose Jaw Times-Herald on October 1, 2010 to mark the 100th anniversary of the first game in Saskatchewan Roughriders’ history. This version has been updated from the original with minor edits.